Don’t order a cappuccino after 11 a.m. Yes, it’s normal to drink your coffee standing at the bar. Don’t ask for a to-go cup. If you order a latte, prepare to be confused.

Anyone visiting Italy for the first time has likely heard one of these lines. In Italy, coffee culture is sacred. It has rules, customs, etiquette, and a tried-and-true menu--but why?

How did coffee get to Italy?

Coffee was first cultivated in Ethiopia and later introduced to Europe through the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire recognised that coffee’s rich flavor and energising properties would make it a profitable industry, and increased cultivation in Yemen for the European market. Venice, a port city, became one of the first European cities to regularly trade for coffee.According to The Great Italian Cafe, when coffee first arrived in Italy, it was regarded as being sinful due to its association with the Islamic religion through the Ottoman Empire. In 1600, Pope Clement VIII was asked to publicly denounce coffee to discourage its consumption. To form a fair verdict, he asked to taste it. In a moment of clarity that has come to be known as the baptism of coffee, the Pope said, “This Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it.” With the Pope’s approval, Italian coffee culture was not only born, but blessed.

The birth of the Italian bar

In pre-unified Italy, coffee brought with it new social opportunities in the form of coffee houses. Coffee was best consumed hot and fresh, so Italy began establishing coffee houses, or cafes--today’s Italian bar. The tradition of coffee houses as social spaces had originated in the Ottoman Empire, but in Italy, it took on a life of its own.The first Italian coffee houses opened in Venice around the end of the 17th century. According to the Great Italian Cafe, “[they] soon became synonymous with comfortable atmosphere, conversation, and good food, this adding romance and sophistication to the coffee experience.” While coffee houses usually welcomed aristocrats, one Venetian coffee house had a reputation for breaking social boundaries.

Caffè Florian: The birth of Italian coffee’s wild social life

Caffè Florian, located in Venice’s Piazza San Marco, was founded in 1720. Today, Caffè Florian is the oldest operating coffee house in the world. In the 1700s, great artists such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, playwright Carlo Goldoni, and writers Giuseppe Parini and Silvio Pellico were known to stop in at the coffee house for intellectual conversations and, of course, coffee. As the first coffee house to allow women, it was frequented by legendary romantic Giacomo Casanova. It later became a favored stop of young aristocrats on the Grand Tour, such as Lord Byron.

Caffè Florian was a meeting place for political radicals before the French Revolution, and later for Venetian patriots during the Venetian Revolution of 1848. As history unfolded, coffee and society wound together at Caffè Florian. The cafe established itself as a meeting place for people from all walks of life, regardless of social class or political beliefs. Caffè Florian set a precedent of what a coffee house could be, and the role it could play in modern social life.

Espresso: The cornerstone of Italian coffee culture

In Italy’s original coffee houses, coffee was usually brewed Turkish style, boiled with spices and sugar in a heated pot. Each cup of Turkish coffee took around five minutes to prepare, not counting the time it took to cool down enough for customers to enjoy it. As demand for coffee grew, so did the need for a more efficient system. Enter: espresso.Espresso is a coffee brewing method in which pressurisation is used to produce a concentrated form of coffee. The name of the process and subsequent beverage come from the Italian verb esprimere, to express, or press out. Many consider espresso to be the purest form of coffee because the quick process does the least damage to coffee grounds. Espresso is made with fine coffee grounds and hot water that is just below boiling temperature, where slower coffee brewing methods use coarser grounds and hotter water. Espresso lets coffee retain the complex, rich flavor of the grounds without burning them or watering them down.

Also read:

- Caffe corretto, an Italian tradition

- Naples seeks UNESCO recognition for Neapolitan espresso coffee culture

The long-awaited invention of espresso

The first iteration of the espresso machine was invented in 1884 by Angelo Moriondo, a Turin-based inventor. Moriondo thought the solution to brewing coffee faster was to have a larger output, so his machine brewed large vats of coffee instead of small, individual cups. His machine was big and bulky, using 1.5 bars of steam-powered pressure to push water through coffee grounds. Though the machine won a bronze medal at the Turin General Exposition in 1884, it was not designed for industrial production and never reached the market.In 1901, Milanese inventor Luigi Bezzerra patented a smaller, single-cup version of Moriondo’s machine. It used steam and two bars of pressure to brew espresso in less than 30 seconds. Bezzera made several user-friendly additions to Moriondo’s machine, including the portafilter, the tapered coffee ground tray with a handle attachment. Though Berezza’s machine was marketable, it produced inconsistent brews and had a hand-operated pressure valve that frequently burned baristas.

Desiderio Pavoni helped Berezza perfect his machine. He added a pressure release valve, making brewing safer and faster for baristas, and a steam wand for frothing milk. Pavoni and Bezzera’s machine was called the Ideale, under the brand La Pavoni. In 1906, their product was introduced to the market, and with it, the term “espresso.”

Though steam power was efficient, it gave coffee a burnt taste. Patents by Francesco Illy and Achille Gaggia in the mid-1930s helped define what good espresso should be. Illy’s patent on the Illetta, a machine powered by pressurised water instead of steam, would become a blueprint for future machines. Its highly pressurised process meant the espresso was pressed without excessive steam, resulting in a richer, unburnt product.

In 1938, Gaggia’s small, efficient, steamless coffee machine took pressurisation to a new level. Where coffee had been expressed by two bars of coffee before, Gaggia’s machine used up to 10 bars to produce truly concentrated espresso--what is now recognised as modern espresso. In addition to its increased concentration, the high-pressure gave espresso its now signature crema, the naturally occurring coffee-foam that forms atop espresso.

Gaggia’s machine reigned supreme in the market until 1961 when the Faema E61 was invented. Ernesto Valente’s stainless-steel machine utilised modern technical innovations to move the burden of espresso-making from the barista to the machine. With Faema E61, pressure, water temperature, and water amounts could be perfectly controlled for a flawless, consistent cup of espresso every time.

Patented technologies by inventors from Moriondo to Valente streamlined espresso machines into the efficient, reliable fixtures Italian bars are known for today.

Coffee culture finds its groove

By the time espresso reached its final form, coffee culture had adapted to meet it. The fast-paced, efficient atmosphere of the Italian bar was matched by small shots of espresso, to be sipped quickly and routinely throughout the day.Also read:

By the mid-1900s, most baristas were able to provide a variety of coffee drinks such as cappuccinos, macchiatos, and caffè latte, by mixing espresso with different amounts of warmed or frothed milk. Economic booms around the same time meant that Italians were spending more time outside of their homes, and bars became a space to grab a pastry for breakfast or a bite to eat later in the day.Also read:

Even though coffee could be ordered, received, and consumed at the bar in a matter of minutes, coffee houses retained the same social atmosphere born in coffee houses like Caffè Florian. Coffee gave Italians a chance to meet up, chat, and enjoy time together--all while consuming a Pope-approved beverage.Bialetti: "Espresso" reaches the home

While the Moka pot is a beloved staple of Italy today, it was born during a dark hour in Italian history: the Fascist Period. According to scholar Jeffrey T. Schnapp, during the Fascist Period, Benito Mussolini declared aluminium to be the “national metal” of Italy. The lightweight, malleable metal was used in production across Italy for home goods and everyday products, as well as military weapons and machinery.

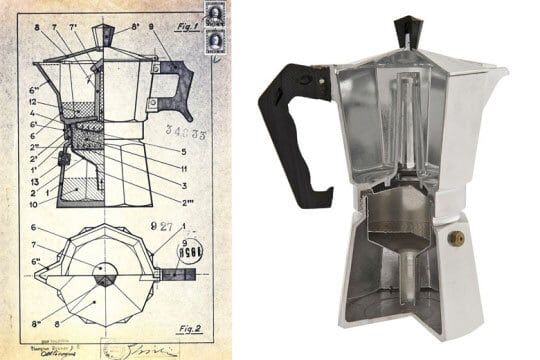

Bialetti had worked in an aluminium factory in France, and upon returning to Italy in 1918, he started his own shop for aluminium goods. His idea for the Moka pot was born after studying his wife’s washing machine, a contraption that used heat pressure to push sudsy water through a spout and into the washbasin. Bialetti realised that the same concept could be used to produce espresso. He went to work in his aluminium shop, and before long, the Moka Pot was born.

The Moka Pot: Sorry, it’s not espresso

The only downside to coffee from a Moka pot is that it isn’t technically espresso. Industrial coffee house machines, such as those made by Gabbia and Valente, use 9 bars of pressure to produce espresso--a perfected number that eventually became a technicality in the definition of espresso. The Moka pot only uses 1.5 bars of pressure. Nonetheless, the Moka pot makes a reliably delicious, unburnt dark coffee.Though the Moka Express doesn’t technically make espresso, most people think it does. This is likely due to the marketing genius of Renato Bialetti, Alfonso’s son, who transformed the Moka Pot from a smart invention into a household staple.

Also read:

Renato Bialetti saw huge economic potential in the Moka Express. He invested in extensive marketing campaigns to expand his reach, using the slogan “in casa un espresso come al bar,” meaning, at home, an espresso like that from a bar.In 1953, competing brands pushed the Bialetti brand to distinguish itself. Renato Bialetti created the company mascot, a little man with a big mustache and one finger in the air, inspired by Alfonso Bialetti.

With the lucky mascot and Renato’s marketing know-how, Bialetti secured its position as the most successful Moka Pot producer in the world. Though the brand has now expanded to other styles of stovetop coffee pots, such as the stainless-steel Kitty and Venus, the Moka Express remains the most famous and beloved pot for homemade “espresso.” In 2011, 90 percent of Italian homes had a Moka Express, according to the New York Times.

Italy’s coffee culture isn’t going anywhere

Whether at a bar or at home, you can count on Italians to drink coffee. But Italian coffee culture is special, a culmination of traditions, customs, and history. Though different regions have their own slight variations on coffee making and bar culture, the fundamentals remain the same: espresso, a standing bar, and a wonderfully hectic, social atmosphere.Also read:

Seattle-based coffee megacorporation Starbucks seems to be taking over the world of coffee. As of 2020, it has more than 30,000 locations worldwide. Visit any major city in the world and you can easily find a Starbucks with a reliable menu of lattes, cappuccinos, Americanos, and a myriad of specialty coffee drinks.While a country’s Starbucks may offer specialty drinks based on location and local tastes, there is usually a core menu of classic American Starbucks coffee drinks. But wait, you ask, aren’t lattes, cappuccinos, and Americanos Italian drinks? The simple answer is yes. Italian words, yes, and Italian drinks, technically--but you would be hard-pressed to find an Italian who claimed Starbucks coffee as remotely Italian. Most Italians want nothing to do with the too-big, too-watery concoctions Americans call “coffee.”

Starbucks has been reluctant to bring business to Italy because Italian coffee culture sternly refuses to be Americanised. Nevertheless, Starbucks has a few locations across Italy, mostly located around Milan and northern Italy. The first Starbucks in Rome was scheduled to open in September of 2020, but with the interruption of the coronavirus pandemic, it seems to have been postponed again. Romans remain unphased.

If there is one thing Italian coffee history proves, it is that coffee culture is Italian culture--it is a testament to the people coming together and enjoying the little things in life; it is a testament to generations of hard work and perseverance to perfect a craft that brings everyday people simple pleasures. Coffee culture is as Italian as espresso itself--and it’s not going anywhere.