As archaeology develops new techniques, more of the Roman city of Falerii Novi is revealed, without digging an inch.

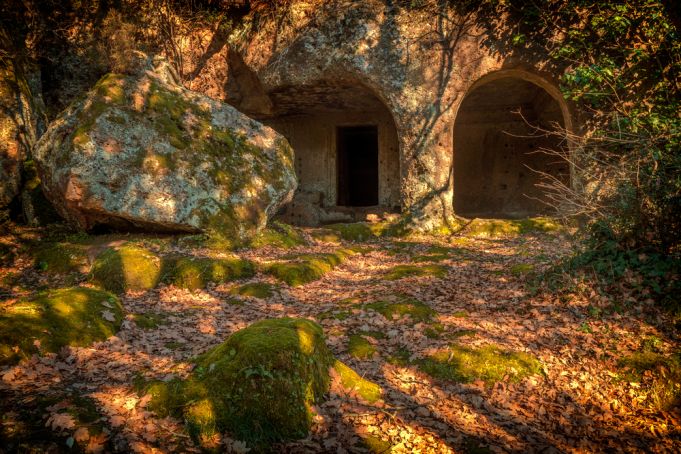

About 50 kilometres to the north of Rome lies a vast site which is encircled by an intact, ancient wall. The 2.4 kilometre-long wall is overgrown with weeds. The area confined by it measures 32 hectares and, apart from a church, an abbey and a farm, is mainly an agricultural field containing mainly corn and figs. In the south-west part of the site are fenced areas for grazing.

After the Romans had destroyed Falerii Veteres, the city of the rebelling Falisci tribe, in 241 BC, they built a new city from scratch, Falerii Novi. This fortified city was subsequently inhabited until the 7th century BC.

Nowadays, neither the buildings nor the bucolic field suggest that this has been an archaeological site for the last two centuries, from its amateur days to today's state-of-the-art technology.

Amateur archaeologists

In 1820 Polish Prince Poniatowski obtained permission from the Catholic Church to excavate the abandoned Roman city of Falerii Novi. The same year, the Church issued its “Editto Pacca”: the first law on cultural patrimony.*

Throughout the decade, two other noblemen, Count Lozano and Count Francesco Mancinelli, would excavate small sections of the large site. One of the findings from these excavations, a bust of Ariadne, is on display in the Louvre museum. Sculpted with extraordinary skill, this masterpiece represents a Dionysian cult.

These excavations, however, were done with the rudimentary methods that were known at the time. And they were done by amateur archaeologists: mostly moneyed aristocrats. As the Bullettino dell’Istituto di Correspondenza Archaeologica already observed in 1829:

“Da quel tempo in poi non ci cessò di far tentative per estrarre altri oggetti da queste terre, ma senza buona riuscita perchè condotti con poca esperienza e regolarità.”

In addition these hobbyists documented their excavations rather poorly. The latter was partly because of the Editto Pacca, which prohibited the export of cultural patrimony. By not recording their findings, the archaeologists could export these artefacts.

From 1969 to 1975 the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio, now in charge of the site, excavated a trench professionally. These excavations uncovered a small part of the ancient street network.

Yet none of the excavations generated a map of the abandoned city ̶ only five per cent of the surface area has been excavated. In 1979, basing himself upon the excavations and their meagre documentation, scholar Ivan di Stefano Manzella, who was working with Università degli Studi della Tuscia di Viterbo, attempted to draw a map. However excavating a site the size of Falerii Novi is very expensive and time-consuming.

Besides, as the recent collapse of the house of gladiators in Pompei illustrates, structures that have been excavated need continuous care otherwise they will crumble. Already in 1976 the Princeton Encyclopaedia of Classical Sites lamented: “The theatre (at Falerii Novi), excavated in 1829, is a mere ghost now” and “An amphitheatre N of the city walls has faded like the theatre.” Today, the excavations done by the Soprintendenza from 1969 to 1975 are already entirely covered with sand.

Non-invasive archaeology

Fortunately, a variety of new techniques, known as non-invasive archaeology, now permit the exploration of the past without disrupting the sites. In 2015 an Italian archaeologist, Cristina Corsi at the University of Cassino, predicted: “The future of preservation is to refrain from digging.”

Falerii Novi, being relatively flat and without any new buildings on it, renders itself exquisitely to such techniques. No development has taken place largely because ownership is divided between the Vatican, the Italian state and the Mancini family which has owned it for generations.

The new techniques use remote sensing to explore large surfaces. In 2005 a team from the British School at Rome used Light Detection and Ranging (LiDar) to scan the entire Falerii Novi site. The scans fine-tuned the 1979 city map done by di Stefano and hinted at a route for religious processions. However LiDar scans revealed only the ground’s upper layers.

Furthermore, dense vegetation, such as that at present around the wall, degrades LiDar accuracy. For instance research in 2007 by a PhD student at the University of North Carolina could not unambiguously identify the city’s decumanus maximus, the principal road connecting the two main gates.

Magnetometry

Barely three years later, the University of Cambridge used another non-invasive technique: magnetometry, for the first time in Italy. The team combined the scans with aerial photography, an early non-invasive technique from the 1960s.

It was possible to get an idea of the city’s overall development and to identify several buildings. Yet, like LiDar, magnetometry reveals only the upper layers. As to the buildings, the research by the British School at Rome in 2010 reported: “The evidence for the individual buildings revealed by the survey is not of sufficient resolution to offer anything more than some general interpretative comments about their character planning.”**

Almost all knowledge of Roman urbanism is based on the extensive excavation of only two cities: Ostia Antica and Pompeii. Yet, apart from its extremely small size, this sample cannot be representative since the first city was a harbour town and the latter a seaside resort. Remote sensing studies, in particular those carried out in Falerii Novi, have now replaced the idea of a standard Roman city comprised of the decumanus maximus (the road running east-west) and the cardo maximus (the other main road running north-south) crossing in the middle by a variety of other planning concepts.

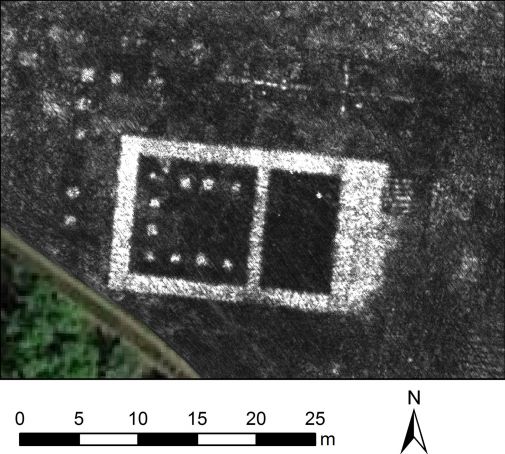

From 2015 to 2017, the University of Cambridge and Ghent University used ground-penetrating radar (GPR) at Falerii Novi. The study was the first high-resolution GPR survey of an entire Roman town. This technique shoots electromagnetic pulses into the earth and registers the signals reflected by underground structures. Thanks to its high resolution, GPR visualises the plots of land which compose a city. And contrary to LiDar and magnetometry GPR reveals a city’s lower, earlier layers.

The GPR study identified buildings no other technique had revealed before. For example, a temple “the size of St Paul’s Cathedral” as an article in The Times headlined in 2017 a macellum (marketplace) and a bath complex. The technique also corrected earlier findings: an open-air piscina (swimming pool) turned out to be a roofed bathing house.

GPR also revealed further details of the road for religious processions identified by the British School at Rome. “Call it a Via Sacra, the road that, in Rome, leads from the Capitoline Hill to the Forum,” Professor Vermeulen from Ghent University says.

But most of all, because GPR can reveal the ground’s lower layers it permits reconstructing a city’s evolution over time. In particular, the survey gives a surprising insight into the way the Romans planned Falerii Novi. As Professor Vermeulen mentioned when interviewed in June this year:

“Up until now, it was thought the city was built following the north-south axis along Via Amerina, the city’s cardo maximus originally linking Rome to Perugia, and a parallel aqueduct. Now it appears the water system was built first and then most of the street network.”

Each of the non-invasive surveys of Falerii Novi challenge the “ground-truthing” concept of archaeology: a deep-rooted idea that there cannot be archaeology without excavation.

A site at risk

Falerii Novi has still not revealed all its secrets, in particular the functioning of its sacred landscape. And non-invasive techniques do not permit objects to be dated. Only excavation does. Therefore, future research will have to combine invasive and non-invasive techniques. In Falerii Novi, the University of Cambridge foresees excavations to deduct the city’s chronology by dating terracotta objects.

The dense vegetation and soil erosion, however, may threaten future research. Particularly the rampart wall is overgrown. Among the vegetation is the European nettle tree, nicknamed spaccapietri because its roots loosen stones from their original position. Although a law forbids ploughing the field below a certain depth, farming has caused soil erosion and old artefacts have come to the surface.

Since the publication of preliminary results of the GPR survey, Ghent University receives calls from all over the world and the lessons learned during the GPR study of Falerii Novi will facilitate similar surveys in other abandoned cities, Roman as well as others.

By Mike Dilien

Published in the September 2020 online edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.

*Editto Pacca: So called after Cardinal Bartolomeo Pacca, cardinal secretary of state under Pope Pius VII, who according to the Treccani encyclopedia was responsible for the 1820 edict on the protection of artistic heritage, which required licences for the excavations of antiquities and trade in objects of art, and authorisation for their restoration.

** Falerii Novi: further survey of the northern extramural area by Sophie Hay, Paul Johnson, Simon Keay and Martin Millet, British School at Rome, 2010.

General Info

View on Map

Falerii Novi: A Roman city revealed by radar

01034 Falerii Novi, VT, Italy