London has Cockney, Liverpool its Scouse, Newcastle its Geordie. Rome has a strange offshoot of Latin, known pejoratively as Romanesco by some, Romano by others or, more usual, Romanaccio. The original form was extant in the time of the Rome poet Gioachino Belli (1791-1863) but was duly supplanted by a lowly equivalent thanks to its simplicity, concision and immediacy. Its expressions pepper everyday discourse. To help the non-native speaker replace bemusement with amusement, here’s a brief linguistic vademecum to some words that no conversation (or argument) can do without.

To start with, some attention-grabbing pet expletives. First the ubiquitous mannaggia: the stress – whether of annoyance, pain or amazement – falls on the second syllable. Once mal ne abbia, or “The devil take it”, this not so much a swear-word as the avoidance of one. Or even more harmlessly – at least compared to Anglo Saxon’s four-letter equivalent – Mannaggia la miseria.

Equally common is li mortacci tua. Dare the rush-hour traffic around Porta Maggiore and the launch of this phrase is almost guaranteed from a rolled-down window or waspish motorcyclist. In fact the derivation is from ancient Roman ancestor worship when forebears were treated with maximum respect. (See a statue in the Montemartini museum of a Roman worthy proudly carrying two heads of departed progenitors tucked fondly beneath his shoulders.) The expression also demonstrates how a swear word redoubles its force when directed against a family member. Alimorte, more in surprise than malice, is a more neutral variant.

Ammazza meaning literally “kill” (ammappa its euphemistic version) is another favourite. Once this bloodthirsty cry of the plebs was directed, with thumbs down, at a losing gladiator, but it has been tamed over time to convey wonder or even admiration as in Ammazza, quant’è bella!

Cazzo has also acquired meanings far removed from the original. With the unshockability and level-headedness of the true linguist, Giuliano Malizia in his Piccolo Dizionario Romanesco devotes two columns to it. While acknowledging the obvious vulgarity, he also notes how it can “express disdain, boredom, wonder, anger or incredulity; or nothing and nobody, a good-for-nothing.” In the mouth of the people its use “reinforces discourse, to make it more credible, real, consistent.” If that’s not defence enough, he then cites its adoption by literary heavyweights Belli, Machiavelli and Leopardi to season their writings.Cacà (defecate) often becomes, less vulgarly, an all-purpose, self-evidently pejorative prefix. So cacadoji is the archetypal doom-monger or oppressive pessimist, a Roman Jonah; cacadubbi labels someone hesitant, cacapepe someone on the touchy side, cacasotto coward, cacasentenze an opinionater. Lastly there is cacaversi, compared to which our own poetaster seems a compliment.

Similar departures from original meaning occur with culo: Vaffanculo as vulgar as one can get (a Roman “Up yours!”) can also express joking incredulity before something unlikely or impossible – as in “Pull the other one!” The opposite of jella, (meaning misfortune) here beginning with a y sound, in avè culo, the noun referring not to the posterior body-part but to luck, perhaps plumpness in that area once being an indicator of wealth. Faccia da culo or faccia come il culo meanwhile expresses anything between cheek and downright shamelessness, as exemplified by certain chat show politicians.

The history of mignotta (for prostitute, as in the title of a Pasolini short story set in Via Casilina) follows an opposite path, its origin in the less pejorative “matris ignotae” (of unknown mother) under which orphans were entered in the public register, or M. ignotae for short.Urban (not to say imperial) arrogance is expressed in a series of other pejoratives for provincials, unlucky or foolish enough to have been born outside the city wall: cafone, originally denoted people from Calabria. Then there are zappaterra (hoer of the earth) and buzzurro, originally denoting itinerant chestnut sellers from Switzerland, then anywhere from the north. Less specific is burino, showing that Romanesco goes back a long way, “buris” being Latin for plough-handle.

Not that things end here. In the spirit of campanilismo (which itself means provincialism – campanile being the village spire) there is noantri – “we others”, in contradistinction to non-Romans everywhere, even within Rome: Trasteverini used to vie with Montosi from across the river in Rione Monti for the title of true sons of the soil, the Roman Forum becoming their annual battleground to dispute that very question.Like Cockney, Romanesco has a genius for short forms. If Cockney tends to leave off the ends of words, then Romanesco leaves off the beginning also. Immondizia (rubbish) becomes 'monnezza; uno turns into 'no, una into 'na; andiamo becomes 'nnamo, etc. The Romanesco èsse (to be) produces: io sò, noi semo, voi sete, loro sò.

As befits the dialect of caput mundi, Romanesco has a hotline back to Latin: abbacchio (lamb), a delicious speciality of cucina romana, derives from ad baculam, “on the stick” the animal was attached to before being led to slaughter; the verb, abbacchiasse, by metaphoric extension means to be laid low or depressed. Pennichella, Rome’s siesta, stems from pendicare, the Latin for to lean; fiottà to lament from fluctuare. Hardly surprising given a Jewish presence going back over two millennia, there are also occasional etymological flashbacks to Hebrew.

As in English, words are often not what they seem. Palo in fare palo has nothing to with a post, but is to stand look-out. If someone calls you selcio he’s not calling you a rock, but insulting your intelligence; dritto means not upright or straight but sly; strozzapreti (priest-strangler) is no criminal but a type of pasta. Buffi (a derivative of buffoon) means debts, anything but funny. Avé le purce in testa may mean to harbour dangerous thoughts rather than lice.

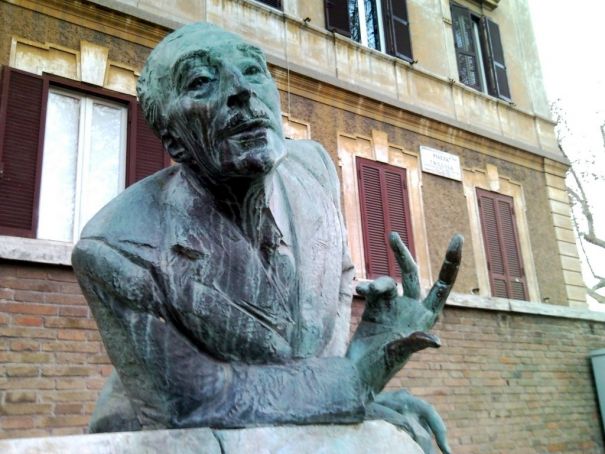

On the literary front Cockney, for all its rhyming slang, has not got much beyond Chas and Dave or Joe Brown and the Bruvvers. Romanesco on the other hand can boast two world-class poets – Belli and Trilussa. Stroll (annà a zonzo) to Trastevere for a binge (abbuffata) and you’ll find a bar named after one poet, a trattoria after another. Putting Romanesco up where it belongs, both have statues. To cite Belli’s own introduction to his Sonnetti romanschi and readjust the language hierarchy still further: “Given their bent for sarcasm, a genius for the rough-and-ready, our populace don’t mince words.”

Martin Bennett

SIDE NOTES

Romanesco has a lyricism all its own, thus vedé tutte le stelle metaphorises pain. The following are all phrases of which any writer would be proud:

Cascarci come una pera cotta (Fall for it like a cooked pear)

Pieno com’un ovo (Full as an egg)

Liscio com’una palla de bijardo (Smooth as a billiard ball)

Parlà come ‘na sveja quanno se scarica (Talk like an alarm-clock)

Barbottà come la pila ar foco (Stutter like a log on a fire)

Avè molte face come ‘na cipolla (Have as many faces as an onion)

Usà una cupola per spegne na canella (Use a dome to put out a candle)

Montà la mosca ar naso (To have a fly up one's nose)

Giuseppe Gioachino Belli (1791-1863) was famous for his Romanesco sonnets which satirised the pursuits of working-class Romans as well as pimps, prostitutes and prelates. He left behind a staggering legacy of 2,279 sonnets, most of which veer between the humorous and the obscene. A white marble statue of the poet acts as a landmark at the Ponte Garibaldi end of Viale Trastevere. See related article.

Born ten years after Belli died, Carlo Alberto Salustri (1873-1950) took up the mantle as the chronicler of Roman life in the city's native dialect. Better known by his pen name of Trilussa (an anagram of his surname), the poet is remembered for his sonnets and poems which feature the petite bourgeoisie and the ruling classes. A statue of Trilussa can also be found in Trastevere, in the square named in his honour.

This article was originally published in the November 2014 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.