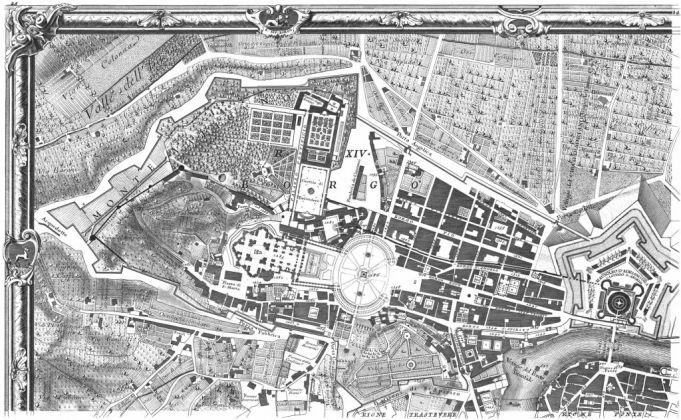

Much of the layout of Renaissance Rome was dictated by the needs of pilgrim routes to St Peter's from all parts of the city.

By Arianna Farina

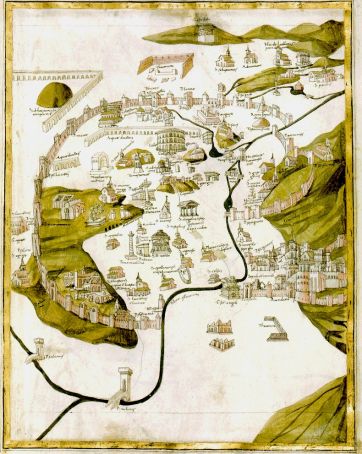

The layout of Rome in the early 15th century was still determined by its mediaeval shape. It was only thanks to the urban planning policies of the great 15th-century popes that the city began to take on the Renaissance form that is still partly visible today.

There is a close relationship between the main thoroughfares of the Renaissance and the current street plan of Rome’s historic centre. Its very survival is an invitation to explore these streets which still retain their architectural styles, as well as the urban and social functions of that great season of Renaissance Rome, and still influences the daily life and the needs of today’s city.

Also read: Must-see museums in Rome

Changing Rome

It was in the second half of the 15th century that the appearance and concept of Rome changed, beginning with its main centres: Borgo on one side and the planned and new Renaissance quarter on the other. It marked the start of the urban planning which was to shape the historic city that we can recognise today.

Borgo, traditionally a pilgrim destination because of the tomb of St Peter, was described in the late 15th century as a devastated and abandoned area. It is said that the very Romans “dared not go to the basilica for fear of being crushed by teetering buildings. Packs of ravenous wolves broke in close to the Vatican in winter.”

Repopulated, saved from degradation and finally connected to the rest of the city, in the first years of the 16th century this zone became a vital residential area of Rome with the creation of a street system of great beauty which remained almost intact up to the the opening of Via della Conciliazione in 20th century, which distorted much of the original street layout.

The Renaissance quarter, particularly in the Ponte and Parione districts, appears today far more faithful to its 16th-century splendour. Once the situation in Borgo had been improved, the citadel and its basilica had to be connected to the “historic” city. At that time there was only one bridge linking this quarter to the other bank of the Tiber: the Ponte degli Angeli.

Precisely because it was the only bridge, it played a role in the tragic event of the 1450 Jubilee, when many people were crushed by the crowds or drowned in the Tiber under the great throng of pilgrims and horses.

Also read: Rome’s most beautiful fountains

Beyond the bridge, from the street called Canale del Ponte, began the city’s main thoroughfares, Via Peregrinorum, Via Papalis and Via Recta, along with the opening of the new Tor di Nona ordered by Sixtus IV and thus called Sistina di Ponte. These were veritable itineraries which, fanned out from the same point, crossing the Renaissance quarter and its districts: the vital centre of Rome, the city of bankers, artisans and merchants.

The Roman Vias

The expression “Via” had a much wider meaning in the 15th century than it does today: indicating routes made up of several streets or roads. Thus we can see in today’s Via dei Banchi Vecchi, Via del Pellegrino and Via di Monserrato the outline of the Via Peregrinorum, the name derived from the pilgrims who trod it. Via del Pellegrino was perhaps the most beautiful. It was lined by splendid palaces and hosted a large number of shops and workshops, especially those of goldsmiths, such that it was still called “Via degli Orefici” as was “Via Florida” up to the 15th century.

Also read: Rome’s decorated houses

This route must have coincided partly with the Via Mercatoria, a particularly important route because it joined Campo dei Fiori with Ponte S. Angelo. It stretched from today’s Via del Pellegrino to Via dei Giubbonari, a residential zone for foreign legations as well as a commerical area, and crossed Campo de’ Fiori, in those days a vital centre of the city thanks to its important market. As its name suggests, Via Mercatoria followed a route through Rome’s commercial areas, as far as the districts of S. Angelo, Regola and Parione, whose streets invoke the ancient trades that were once located there: Via dei Leutari, Via dei Cappellari, Via dei Giubbonari, Via dei Chiavari or Via dei Baullari.

The outline of Via dei Banchi Nuovi and Via del Governo Vecchio corresponded to the Via Papalis, so named because it marked the traditional route taken by the pope during festivities and religious ceremonies. The road connected the Lateran to the Vatican, passing through the Canale di Ponte and then through Via del Governo Vecchio, Largo Argentina, the Campidoglio and the Colosseum.

Popes did not always follow the same route, but – apart from a few deviations – they would always choose the mercantile streets for ceremonial and also representative purposes. It was here that the market of Piazza Navona was born in 1477 under Sixtus IV, becoming the “third urban pole”.

The Via Recta corresponded to today’s Via dei Coronari, the first straight street in the city guaranteeing direct access to the Vatican for pilgrims.

This was also the longest route, as it passed through the Ponte and Campo Marzio districts along Via delle Coppelle, Via del Collegio Capranico and Via di Colonna. The last stretch of the road as far as Via Panico was known as “imago Ponte” for one of Rome’s most important wayside shrines. This street was totally dedicated to crafts, as well as to pilgrimage and the spin-off market it produced. Thanks to the concentration of sellers of wreaths and religious articles, it was a sales point for sacred wares, as well as being a main thoroughfare.

Also read: Rome's secret libraries

There was also Via di Tordinona or Sistina di Ponte, which is now much narrower because of the embankments built along the Tiber after the floods of 1888. We should not forget the urban utopia of Via Giulia, the well-known architectural feat of Julius II and Bramante, giving pilgrims coming from Trastevere and heading for the Vatican a new and splendid route.

Also read: Discover Rome's secret courtyards

In spite of some demolition work and the opening of Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, much of the street system and its original appearance are still visible today. This brief list shows how much of the original layout of the Rome of the popes – much of which still survives today – was dictated by the demands for access by pilgrims.

Also read: La Fornarina: who was Raphael's mysterious lover?

Rome’s richness is due also to its earlier beauty, but in this case it is not isolated in its ruins or on display in museums. There is instead a fusion of past and present, a continuing function and traffic system, a close connection between the urban demands of two societies totally separated by the passage of time, which renders any one of these streets a witness to change, but also to continuity. Knowing that the same streets were trodden by visitors and Romans centuries ago helps one integrate the ancient with contemporary city and gain a better understanding of the concepts at the origins of its creation. These streets represent far-off memories, ancient and present-day aspects, which make the journey toward St Peter even richer and more precious.

This article was published in the January edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.

Main ph: Matthew Dixon / Shutterstock.com