An exhibition at the Colosseum traces the Roman empire's “last period of greatness” under the 40-year reign of the Severans.

A new exhibition at the Colosseum pays tribute to the Severans, Rome’s fourth and final dynasty which ruled from 193-235 AD and which was arguably its most controversial.

The catalogue hails the Severans as reformist, displaying in papyrus the Edict of Caracalla, or Antonine Constitution, conferring universal citizenship upon the empire's subjects. Yet the 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon blamed the Severans for imposing a militarised monarchy whose 40-year rule eroded the powers of the senate.

With 111 of the senate's number liquidated or dispossessed – 18 per cent of their 600 total in the senate – the political balance shifted to the often unruly, ever more costly legions. Post-Severan emperors would tumble like nine-pins as army factions promoted their man or just as often did away with him if he failed to do their bidding.

The neatly-trimmed hair and Greek-philosopher-type beard of Marcus Aurelius are shared by Septimus – his attempt to confer authority and due continuity on what would in modern parlance be termed a military coup. Indeed in his first speech to the senate, Septimus declared Commodus, the son of Marcus Aurelius, a god, in front of the very dignitaries Commodus (of Gladiator fame) had threatened to decapitate.

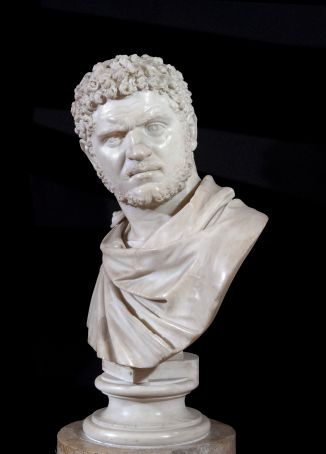

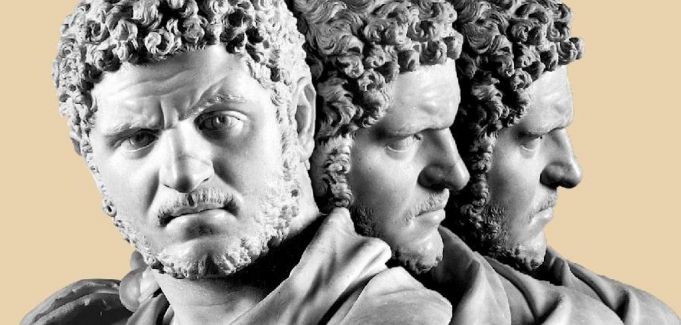

One bust is of a childhood Geta. Glaring sideways, Caracalla, who had Geta murdered, boasts two busts. Geta was then erased from public memory, his likenesses pulverised or, in a family fresco, reduced to an anonymous smudge. Caracalla, Gibbon’s “enemy of mankind”, would also have an untimely end, killed in a plot involving Macrinus, head of the Pretorian Guard.

Arriving in Rome a year later, the youth would become a cross-dresser, husband to first a series of women, then to a charioteer, then to a vestal virgin. This between suffocating dinner-guests with rose-petals and forcing senators to attend ceremonies anything but traditionally Roman. For damage limitation, Julia Mesa persuaded him to share the throne with her other grandson, the strictly Roman 13-year-old Alexander Severus who, in a further sleight of alternative fact, was also passed off as a son of Caracalla.

From busts to buildings: models of Leptus Magna, Septimus's home town, then of his triumphal arch in the Forum, virtual imagery enabling the visitor to examine closely the scenes too high up on the real thing. Those triumphs against the Parthians, their captives lined in chains below, didn’t last. In an early example of imperial overstretch, the Persian Sassanids were waiting in the wings to win back lands from the Romans as the empire began to collapse, while in the north of England guerrilla tactics by the local tribes drove the legions back behind Hadrian’s wall. During a rest in campaigning against the Caledonians (or Scots), Septimus died in Eboracum (York) in 2011.

Outdoing plastic casts are the Urban Landscape section’s 3D videos: Admire Eliogabalus’s temple (in the Roman Forum) and then Septimus's Septizodium with all its statuary and fountains. There’s also a drone’s-eye view of Severus’s Arch topped by a golden seven-horsed chariot. A second video pieces back together part of the Forum Urbis, the marble map once attached in 150 slabs to the Templum Pacis, the area now largely occupied by the S. Cosma e Damiano church. Only 15 per cent – 1,186 chunks – survived depredation following Rome’s fall. The wall-holes still perforate the SS. Cosma and Damiano church façade.

From stone, via Egypt, to papyrus. The anachronistic-sounding Antonine Constitution is explained on video by Caracalla. The constitution conferred universal citizenship rights, yes. But also the responsibility to pay taxes to support the burgeoning military and the massive building and restoration projects following Commodus’s fire-prone rule. As the catalogue mentions, plagues and smallpox in previous decades had drastically eroded the tax-base. Here, at one stroke, was a means of widening it.

And luxuries? Indicating how seriously Romans took their pleasures, from New York’s Met Museum comes a tray-handle engraved with the triumph of Bacchus. With the potential to inflate cocktail prices, from Germany calyxes, cups and beakers demonstrate glassware as an art form which our mass technology has lost. More down-market is some Tunisian earthenware, but whose cupids, birds and a musical monkey combine to make drinking cinematic.

Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a brilliantly grotesque if majestically worded helter-skelter of events, can read like a fiction; here in recently or not-so-recently excavated marble and travertine is its confirmation as fascinating fact.

General Info

View on Map

The Colosseum hosts the Severans

00184 Roma RM, Italia