The Romans, through the Latin language and the far-reaching cultural influences of the ancient Roman empire, are arguably founders of Western culture.

Their position as members of an ancient Mediterranean society meant that any notions of race as we know it today did not yet exist. One main reason for this is that they primarily were not what we would now consider white.

Modern anthropologists have published bodies of research which have been able to provide a full genetic history of Rome demonstrating that as of the 1st century CE, the city-state was actually populated by many peoples of Near Eastern and North African origin.

Archeological and literary sources have contributed to even more subtle details in the wider picture—even Virgil wrote in the Aeneid that Rome’s progenitors were Trojans, Anatolians, and other Asian and Middle Eastern peoples who crossed the sea to create a new society.

Ancient roman city of Tindarys, Sicily.

The remains of houses and temples across Sicily and southern Italy clearly illustrate the history of Asian Greeks and Middle Eastern Phoenicians integrating with Italic tribes as early as the 7th century BCE.

Many scholars suggest that ancient Romans did not have any concept of race as a category. Although this is not quite true, they had several words which distinguished people according to family lineage and ancestry which, although often overlapping with race, was not strictly race-based.

The main organizing principle was geographic so that the Romans could divide tribes into groups, such as the Celtic Gauls and the “Punic” Phoenicians, while they had a variety of other words to describe physical appearance and color in socially neutral terms.

Sicilian сeramic vases of a King and Queen in the form of heads.

Roman antiquity was much more diverse and polychromatic than most of us are willing to admit, and the impact it had on the generations in the following centuries seems to have escaped modern common knowledge.

So how did we end up with the idea that “it is a mere legend that large masses of migrants came into [Italy]” from the Race Manifesto of 1938?

We have whitewashed history for the sake of European imperialism

Patriots were struggling to bring forth a unified Italian identity at the dawn of the 20th century. When Giuseppe Garibaldi unified the various contrasting regions of Italy into a single nation-state, the anticipation for a new era of glory grew immensely.

However, economic, diplomatic, and cultural outcomes were lacking decades later. Nationalists were searching for something to boost public morale by making Italy seem strong and competitive on the global stage.

Commemorative stamp of the centenary of the battle of Dijon fought and won by Giuseppe Garibaldi. Photo credit: Marino14 / Shutterstock.com

Religion, the Renaissance, and the long tradition of democratic republicanism were all viable contenders to become the rhetoric behind a stronger unification.

However, the debate eventually settled on the classical legacy of ancient Rome due to its former presence at the center of European affairs.

With this history in mind, the narrative was consciously woven around one central intention: to make Italy great again.

That is to say, demonstrating its global aspirations would mean asserting Italy’s modern role in European imperialism.

In 1912, an attack was launched against Ottoman Libya. As Janzur was bombed, Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio wrote “Songs of Our Exploits Overseas” in which he called on all patriots to reconnect with the “eternal memory” of the ancient past and overcome the suffocating “curse of centuries” to set out and dominate the world under a new flag.

Other nationalists followed suit, often concentrating on Italy as the bringer of new civilizations.

The journalist Enrico Corradini went as far as suggesting that there was a hidden Roman road beneath the Mediterranean Sea, referred to by many writers by its ancient Roman name, Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea), which linked modern Italy to the African colonies over which Italy had a “historic claim”.

Italy’s propaganda held racist overtones. Over the generations, people from all sides of the Mediterranean had been intermingling with one another, from Tangier to Istanbul to Rome, to the point that the Italian peninsula’s inhabitants could not feel certain of their own ethnic “purity”.

Ironically, Italian intellectuals were nervous about presenting themselves as a homogenous group as a result of the nation’s geography.

To remedy this, philosophers such as Julius Evola generated esoteric theories about an “Aryan super-race” which held a sort of spiritual nobility that supposedly always existed in Italy, including since Roman times, which gave “true Italians” the moral right to dominate non-Europeans.

Combined with the rising popularity of fascism, erasing color from history seemed to come naturally.

The rise of fascism solidified our modern ideas of ancient Roman “whiteness”

Mussolini's Square Colosseum in the EUR district of Rome.

Benito Mussolini’s rise to power perpetuated ancient whitewashing. His ideology wielded Roman imagery such as the eagle, the fasci, and a fictitious ancient salute, much more aggressively than the Italian intellectuals and political leaders which came before him.

Simultaneously, Mussolini opportunistically supported the field of race science by encouraging anthropologists and eugenicists to produce “empirical” evidence for what he called the “innate vitality” of the Italian race.

In 1934, Mussolini’s regime commissioned an installation which embodied a vision for Italians’ destiny as the rightful inheritors of an Aryan Roman empire.

Architect Antonio Munoz realized the work which included five maps, four of which displayed the evolution of the Roman empire from the age of Romulus to Trajan while the final image depicted Mussolini’s own plan to obtain control over the entirety of East Africa.

The maps were displayed along the exterior walls of the ancient Basilica di Massenzio in the Roman Forum.

Munoz also designed his maps according to an anachronistic and ideologically charged color scheme which he rooted in “race science” where everything inside the “Italian” world was designated by white travertine marble while everything beyond it was black.

Mussolini’s use of classical antiquity may be considered a minor quirk of Italian fascism, but the uncomfortable truth is that every major European power has leaned on ancient Rome to draw comparisons of a similar sort.

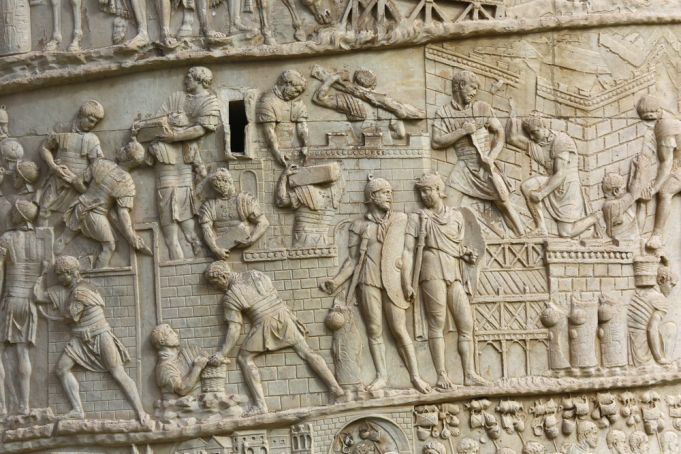

Detail from Trajan's Column in Rome.

British intellectuals across the political spectrum, including Rudyard Kipling, Lord Curzon, and Arthur Balfour, all cited Rome as the moral justification of British imperialism on the basis that they were “bringing civilization” to brown and black natives.

Latin and neoclassical figures were being used to celebrate European victories over various nonwhite populations.

The Western imagination has embedded the myth of a white Rome so deeply that it has even found a wider audience outside of Europe.

The founding fathers of the United States, for example, highly regarded the ancient republic, and many of them greatly admired Cicero as a defender of justice while others, such as Alexander Hamilton, considered Cato the Younger as the very incarnation of liberty.

Anti-abolitionists also eventually turned to Rome to justify white supremacy.

Thomas Roderick Dew, a revered professor from Virginia, argued that ancient Rome was able to thrive only because the “slaves were more numerous than the freemen”.

Following emancipation in 1916, there were widespread fears among white Americans which Madison Grant, a lawyer and zoologist, claimed that people of color would end up “breeding out their masters…[as] in the declining days of the Roman Republic”.

The idea of ancient Rome has somehow generated a kind of racist discourse on moral grounds, and it is crucial to acknowledge that despite the differences between Italian fascism, European colonialism, and American pro-slavery groups, they have all managed to contribute to a fantasy idea of Rome’s whiteness which is still a major feature of Western civilization.

High-profile figures from Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Antonio Gramsci have worked in various attempts to repudiate this abuse of history.

However, two lesser-known arguments must also be acknowledged to reconcile modern thought with history.

First, ancient Romans did not have the sense of race in the same modern sense of the word, and second, the ancient Roman empire, unlike modern equivalents, was one which was led by key figures who, in today’s terms, would be considered nonwhite people.

Common misconceptions: Ancestral discrimination rather than race

The consensus on the matter of race in the modern day is now so great that even Craig Venter, the pioneer of DNA sequencing, has said that race conceptually has “no genetic or scientific basis”.

Subsequently, turning to the ancient world means that it is necessary to dispel any lingering suspicions that race is a legitimate scientific concept.

Our imagination of race typically occurs through various narratives of whiteness, and the idea of whiteness has strong cultural connotations.

Cultural theorists, like Edward Said, agree that European powers invented the concept of whiteness and orientalism as a pseudoscientific justification for imperial expansion. That is, it is both an explanation and condition for European supremacy, meaning that all non-white “others” had to fall under correlating inferior concepts, which is the system that serves as the basis for modern racism.

Roman writers were admittedly guilty of what we would now call “racialism”, meaning that they considered certain cultures of certain areas to exhibit certain behavioral traits.

Interestingly, though, this was tied to the weather in the location of geographic origin more than the skin color of individual people.

For example, Vitruvius wrote that Africans were healthy and intelligent, but that the sun had dried up their blood which he claimed had made them cowardly.

The Germans, however, were considered as stupid people who had a strong and healthy blood flow due to dealing with the cold weather.

Crucially, there was no ascertained hierarchy which established that no particular skin color was seen as above the others. There is no evidence that Roman institutions attempted to develop race-based judgments into a system, let alone a science with a claim to objectivity.

In fact, figures such as Juvenal despised Africans, but held a reserved disgust for Germanic tribes on account of their pale skin and blue eyes, considering them unnatural degenerates.

Modern societies often fail to grasp the importance of these distinctions.

Additionally, the abundance of plain white marble statues which remain from Roman antiquity are often mistaken as evidence that Roman populations preferred white bodies to Black ones, disregarding the variety of grey, pink, and green marble that has been discovered and the literary sources which inform us that most works were also painted in polychrome blues, reds, and yellows.

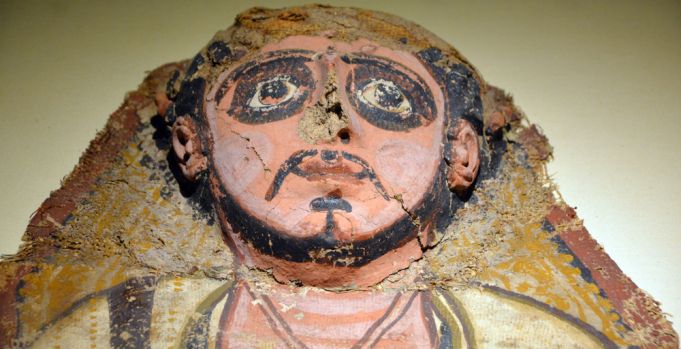

Fayum portraits is the modern term given to a type of naturalistic painted portrait on wooden boards attached to Upper class mummies from Roman Egypt. Photo credit: meunierd / Shutterstock.com

Moreover, Roman ideals of beauty were not exclusively white. The Fayum portraits between the 1st and 3rd centuries depict brown-skinned, dark-eyed people in a manner that explicitly suggests them to be objects of admiration.

There are also accounts of poets leaving numerous odes which celebrate Black bodies, such as Asclepiades who compares the object of his desire to a coal that comes to “glow like rosebuds” when heated.

There is currently no evidence suggesting that African Romans experienced serious discrimination based on the color of their skin, and rather had to struggle to overcome their reputation for being “provincial”.

The imperial elite was also multiethnic and based on ancestry to the founding nobility, meaning that it was difficult for citizens born in more distant territories to climb the social ladder, but it was not impossible and still not based on racial discrimination.

Understanding why modern colonial powers turned to Rome for inspiration is not difficult, but the whitewashing of history to generate a moral justification of modern imperialism is a bit more complex.

Demonstrator dressed as an eagle on the Capitol Mall during a Pro-Trump rally that turned into a riot on 6 January 2020. Photo credit: Bryan Regan / Shutterstock.com

The basis of ancient Roman xenophobia and racialism is far removed from the modern sense of the concepts, but it has not stopped far-right political groups from reproducing a distorted and racist version of the classical past to this day.

In fact, the American Identity Movement, a now-defunct neo-Nazi group, started to use classical statues as avatars in their forums, and this trope has since become a hallmark of white supremacists.

Classicist Donna Zuckerberg warned in 2018 that these groups are “[turning] the ancient world into a meme to project their ideology into the world”.

In 2017, far-right activists marched in Charlottesville behind images of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, over which they used phrases like, “Every Month is White History Month” and “Protect your Heritage”.

The Washington, D.C. Capitol rioters of 2021 donned T-shirts with Rome’s golden aquila and tattoos of SPQR, the motto of the ancient republic.

We need to restore color to the classical world

The urgent question of redeeming the ancient world from colonial bias has presented cultural practitioners with an unprecedented chance to help the wider public engage with an idea of Rome which is more diverse, realistic, and interesting than the monochrome fantasy concocted in our recent past.

White supremacy groups storming centers of Western governance has not merely presented a specific issue: dismantling this racist view may play a vital role in strengthening our democracies.

First and foremost, the equation of white marble with beauty is not an inherent truth and must be dismantled as a dangerous construct which continues to influence white supremacist ideas today.

Roman marble sculptures from the Vatican Museums. Photocredit: IR Stone / Shutterstock.com

Marble was a precious material for the Greek and Roman artisans, but it was also largely considered a canvas rather than the finished product for sculpture, which was often painted in various shades of gold, black, brown, and red among other colors.

Most museums and art history textbooks contain predominantly white displays of skin tone when it comes to classical statues and sarcophagi, which has an enormous impact on the way we view the ancient world up until now.

We must restore our perception of color to the ancient world.

Then, and only then, we may begin to strengthen the unity of our modern notions of democracy and dismantle racist ideas of racial hierarchies in global society.