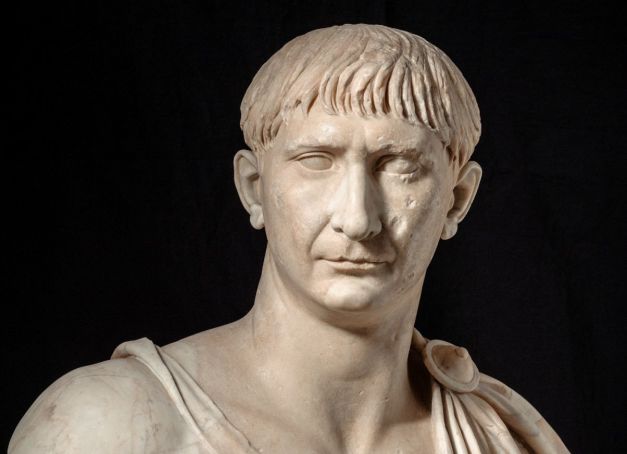

Emperor Trajan is celebrated on the 1,900th anniversary of his death with a multimedia exhibition at Trajan's Markets in Rome.

By Martin Bennett

To begin at the end. Passing the black curtain of the gold portal that forms the entrance of the exhibition Traiano. Costruire l’Impero, creare l’Europa at Trajan's Markets, you find yourself inside the facsimile of Trajan's tomb, the real version being some 100 m away in the pedestal of Trajan’s Column.

The late emperor (53-117 AD) addresses you from the hereafter, courtesy of a video screened overhead. He gives a brief life history: how, past 40, he was a general and legate in lower Germany when he received news of the death of Emperor Nerva, his adopted father, and was summoned to Rome to succeed.

Lifetime of firsts

He lists a lifetime of firsts – first emperor to be born outside Rome (he was born in Spain), first to cross the Danube, and so on, culminating in the first emperor to have extended the empire to its utmost limit before or afterwards. Reaching Babylon he’d offer sacrifices in the house where Alexander had died. “Were I still young, I would’ve crossed to India also,” Trajan, via Latin historian Dion Cassius, quotes himself. Only for time and death to catch up with him while out on campaign. His second (Parthian) triumph he would attend posthumously after dying of a stroke; his ashes, having been brought from the east, were duly deposited under his column.

The second room of the exhibition or, one might say, the show (its curators use the word “pop”) echoes with cheers of the crowd mingling with a non-stop shower of roses; the model of the triumphal procession stretching across the floor almost comes alive. A written commentary notes the three qualifications for a triumph decreed by the senate: to have killed in battle 5,000 enemies, to have brought the soldiers safely home, to have extended the imperial frontiers. Bringing home adulation’s limits, in the room’s corner is Constantine’s marble head, once in the imperial portrait gallery of Trajan's Forum. Archaeologists found it blocking a public sewer. One theory goes that, following a revolt in 326 AD, insurgents added insult to injury by using it as a cleaning device, a sort of upmarket, out-size pumice stone.

Imperial dress-code

The next section stars a bronze mask on loan from Holland’s Valkhof Museum in Nijmegen, once the site of a Roman army camp, the head having been dredged up from a nearby river. Here’s someone, it suggests across millennia, not to mess with. Every intrepid, hard-won wrinkle is powerfully intact. The sidewall video meanwhile elaborates imperial dress-code: purples, gold, magenta, a reminder that the trans-European selection of busts in the photographs to the left would have once been coloured too.

But glory costs. Farther on are four funeral stones of soldiers or officials who died during Trajan’s campaigns (Dacian, Syrian, Parthian). Trajan is present only in part. A massive fragment of heroic jaw and chin, his sculpted head stops above the upper lip.

Next door is a model of Tropaeum Traiani, the Roman world’s largest triumphal monument, celebrating the emperor's subjugation of Dacia. Above us is a wheeling video of a bleak Romanian landscape stretching far away as muffled drumbeats and a searing wind complete the effect of the Dacian campaign. Triumph, and, as evinced by the sculpted Dacian captives on the monument’s roof, perhaps a way of rubbing the faces of the vanquished in the scale of their defeat.

Roman engineers

Across the museum atrium, lest victory be forgotten, appear more Dacians. The four marble figures with their Dacian headwear once decorated the Basilica Ulpia’s façade, the building which Dacian slave-labour made possible in the first place. Not to mention a Roman war chest of 250,000 kg of gold and twice that in silver, a motive for the five-year campaign. From the presently-closed Museo di Civiltà Romana in Rome's EUR district come plaster casts of six of the 155 scenes of Trajan’s hill-high column. Here’s a citadel topped with the skewered heads of Roman legionaries. Here soldiers ford a river and Trajan delivers an adlocutio on the far bank. Primitive clubs versus honed steel, another cast shows Dacians getting the worst of it; actually their 200,000 army deployed cavalry, archers and siege weaponry thanks to Roman engineers who had defected to the Dacian camp under former Emperor Domitian. Then we see Dacians in their besieged capital: “Give me freedom or give me death.” Some are being handed poison by their leader. Last up is Dacian king Decalabus, slitting his throat beneath a tree with scythe-like dagger or falx. The same newsreel does not show Trajan sending the head of Decalabus to the senate back to Rome as proof of victory.

Trajan's Women

Greeted by a giant female head from Trajan’s Forum, one reaches a section dedicated to Trajan’s Women. Plotina, wife of Trajan and first lady, would accompany him on campaigns and later, in death, share his funeral chamber. Her image also shared the same coins, here deified as Vesta, the hearth goddess while on the other side presides Caesar Augustus Germanicus Dacius consul VI Pater Patriae, a.k.a. Trajan. Busts of sister Marciana and niece Matidia included, the fashion links are there not only in the ornate hairstyles, but even more spectacularly in a Bulgari necklace. 20th century moda incorporates three ancient coins of gold (aurus), silver (denarius) and bronze (quadrans) in its platinum. Arguably though, the star here, and a good mentor for female empowerment in the first century AD, is Matidia Minore, Matidia’s daughter: high tech equips her illuminated marble head with a voice narrating in both Italian and slightly unrealistic American-English a gamut of business and charity activities.

Trajan at home

In the section Trajan at home, archaeology meets speleology. A partly drone-filmed video takes you down, down, down a manhole on the Aventine hill to what was probably Trajan’s Domus before he became emperor. For his private imperial villa he chose Arcinazzo Romano, about 50 km east of Rome. In a veering video taken from a helicopter, a section of its palatial brickwork is just visible among luxuriant foliage and a tumbling waterfall. While the interior decoration of the Aventine Domus is almost miraculously unchanged, that of the imperial villa is a jigsaw of countless pieces which the archaeologists are still in the throes of re-assembling.

The exhibition runs until 16 September at Trajan's Markets.

One last treat remains. Venture down into Trajan Market’s piccolo emisfero, and a short film explores how Trajan’s reputation was elaborated upon through to mediaeval and Renaissance times. There is Trajan, optimus princeps, simply the best, who, to cite Pliny the Younger: “ordered us [Romans] to be happy, and so we will be.” On Gregory the Great’s prayerful intercession, there’s Trajan elevated from hell to paradiso where Dante places him next to King David as an archetype of the just ruler. 1,900 years after his death, in the catalogue there’s Trajan recast as ”Constructor of Empire, Creator of Europe”. Any number of great works, not just completed against the odds but which have lasted millennia.

Yet one can’t help feeling a pang for those unsung Dacian captives – 50,000 marched in chains to Rome, 10,000 dying in the Colosseum along with 11,000 animals in 123 days of celebratory “games”. Historian Edward Gibbon puts it rather more majestically. The same Trajan who in Dante stops his march to war to humbly honour a widow’s appeal for justice was also, cautions Gibbon, “ambitious for fame. As long as mankind shall continue to bestow more liberal applause on their destroyers than on their benefactors, the thirst for military glory will ever be a vice of the most exalted characters.” The film concludes, “Now it’s your turn to continue the story?” A good question. This exhibition/show/history lesson par excellence gives ample and fascinating food for thought.

The exhibition Traiano. Costruire l’Impero, creare l’Europa runs until 16 September at Trajan's Markets, Via IV Novembre 94.

General Info

View on Map

Rome remembers Emperor Trajan

Via Quattro Novembre, 94, 00187 Roma RM, Italy