American artists chose Rome over Paris in the immediate postwar years

The Roman art world was enmeshed in a web of political allegiances, which Life caricatured in an earlier article published in 1949. After years of Fascism, which isolated the city from the rest of world, Italian artists, often banding together in associations, such as Il Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, attempted to renew the avant-garde and establish productive links with artistic movements elsewhere. Their efforts faltered in 1948, when Palmiro Togliatti, head of the Partito Communista Italiano (PCI), denounced an exhibition of abstract paintings in Bologna as “monstrous things.” This broadside created major faults in the Italian art world, essentially forbidding Communist artists from painting in an abstract idiom.

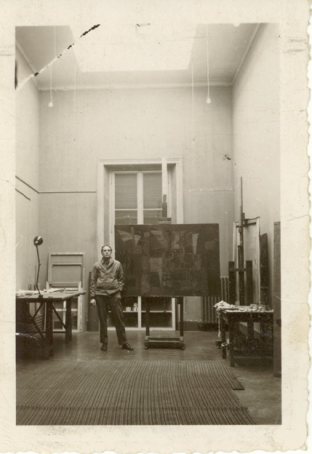

While these artists pursued abstraction on shaky ground, within a matrix of conflicting loyalties, Scarpitta, despite his difficulties, remembers a porous, fluid atmosphere of exchange. “The American Academy was a survival space. On the outside, or shall we say on the inside, was Italy, humanity, politics, the competition, let's say competition; and that's where I began with the abstract movement in Italy. The Communist Party didn't like our attitude toward art, but accepted us because we had a certain crescendo, a certain popularity. We also made friends among leaders of the Communist Party who were not that sectarian about their approach to art.”

Dorazio was part of a group of younger Italian artists who banded together as Forma 1, publishing a manifesto in 1947 declaring that they were “formalists and Marxists convinced that the terms Marxism and formalism are not irreconcilable.” They proposed to mediate between abstraction and realism.

Guston, who met Dorazio in 1948, was no stranger to art in the service of leftist social and political agendas. His enthusiasm for the Mexican muralists was tied up in the activities of the Los Angeles branch of the John Reed Club, a Marxist study group, which encouraged artists to abandon the idea that art can exist for art’s sake. The fragmentary motifs in Tormentors – echoes of shoe soles, two by fours, the hoods worn by the Ku Klux Klan – hark back to earlier figurative paintings depicting social and political injustice. In the year before he came to Rome, Guston painted Porch II, in which he broke down figures and compressed pictorial space to convey the horror of the Nazi death camps. In Rome, Guston continued this process of dismantling, stripping away the form and piling on paint, obscuring or erasing shapes with gestural brushstrokes.

The cultural historian Mary Louise Pratt offers a useful framework to explain the complexity of American experience in Rome after the war. She has coined the term “contact zones” to describe “social spaces where cultures meet, inform each other in uneven ways, and where they clash and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power.” A “contact zone” allows for interaction, so that cultural boundaries can be broken and transgressed. We might consider postwar Rome a “contact zone” in which, despite mutual admiration, Americans and Italians faced off and exchanged ideas in a relationship shaped by postwar reconstruction and the Cold War. The move to abstraction betrays signs of “transculturation,” one of the strategies identified by Pratt in the “contact zone.” First defined by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz in 1947, transculturation describes the process whereby members of subordinated or marginal groups select and invent from materials transmitted by a dominant metropolitan culture.

Inured to the artistic hegemony of New York, we usually assume that the transmission of abstraction must have flowed only in one direction across the Atlantic. Yet, despite its newfound superpower status after the war and the growing authority of its modern art, the United States remained a cultural upstart with respect to the august traditions of old Europe. Guston, an admirer of Piero della Francesca and Giorgio de Chirico, arrived in Rome in awe of Italy’s cultural preeminence. Impressed by the way in which Dorazio and others reconciled their commitment to Marxism with their ongoing exploration of abstraction, Guston may have recognised there a way to create a similar balance in his own work.

“Well, I lived not as an American; I lived with the Italians. I wasn't just a tourist. I set up a studio and lived there. I associated with most of the Italian artists. I knew them all: Afro [Basaldella] and Mirko [Basaldella] and [Renato] Guttuso.”

He had his first show in Rome sponsored by these Italian artists. Guttuso wrote the preface for the accompanying catalogue. Carone later underlined the benefits of that “aesthetic climate, working with the Italian painters,” and his attentiveness to their fluid, non-doctrinaire strategies. In championing Carone’s abstract work, Guttuso, the most prominent artist to remain faithful to the party line, broke ranks with PCI diktats. In his text, Guttuso insisted that all the paintings in the exhibition were “profoundly Italian in character.”

In restoring Rome to its rightful place as an artistic centre after the war, we can begin to unpack a more complete picture of the productive exchanges between American and Italian artists and their enduring impact on abstraction in both countries.

Published in the November 2017 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine. This is a shortened version of a recent talk at the American Academy in Rome by Peter Benson Miller, the Andrew Heiskell Arts Director at the American Academy in Rome, www.aarome.org.

General Info

View on Map

Painting in the contact zone: American artists in postwar Rome

Via Angelo Masina, 5, 00153 Roma RM, Italy