The president of the American University of Rome outlines how Lampedusa could turn to archaeology to help it through difficult times.

Richard Hodges

Flying south of Agrigento the blue begins, even on All Saints' Day. An Ionian light, it is the ravishing glory of the Middle Sea. I went to Lampedusa in November 2015 in the footsteps of Pope Francis and political grandees, conscious that this miniscule Italian outpost had borne a heavy burden as it grappled with the lives and accursed deaths of thousands of migrants. Here, over the past 30 years, tragedy has mixed with mass tourism to give Lampedusa a peculiar notoriety in Italy and abroad. I came to offer the help of our students at the American University of Rome. Could they contribute to writing grants, preparing programmes, and even running projects in the field of internal relations, especially immigration issues, shouldering a little of the island’s burden? Speaking English, Italian and in some cases Arabic, might our students make a small contribution as Europe is challenged by a migration of biblical proportions? For our students, being embedded in the philanthropic front line might provide them with experience to engage in still greater challenges, because this migration is not set to cease soon.

Mayor Giusi Nicolini

As the propeller plane settled towards the airfield, the shadowy outline of Tunisia about 100 km to the south became clear. The mayor was in her office. Giusi Nicolini has become a national figure, an articulate advocate for support for her people facing waves of impoverished, bewildered migrants from Libya. A self-confident woman who eagerly listens, she is not a natural politician, and is all the more fascinating for it. She is curious to hear how our university might help, but is not instinctively enthusiastic about promoting herself or her island’s circumstances. Her primary problem is to combat the kind of corruption that has been endemic in Italy, and to improve the infrastructure on the island. But, then I mentioned the name of Thomas Ashby, my distant (legendary) forebear as director of the British School at Rome – the first person to survey the archaeological remains on the Pelágie lslands (Lampedusa, Linosa and the uninhabited islet of Lampione) and the mayor’s eyes beamed with delight. Ashby landed from HMS Banshee with the support of Rear Admiral Sir Assheton Curzon-Howe to make his survey in June 1909.

Tourism

Lampedusa has grown its tourism since the first airfield was constructed in the 1960s. Perversely after Colonel Ghaddafi fired two scud missiles at the island’s US base in 1986, tourism rocketed upwards. Exact numbers of visitors to Lampedusa and its sister island, the extinct volcano of Linosa, appear to be vague. But there are roughly 70,000 beds offered by the island’s 6,000 inhabitants, and about 1,000 young Lampedusans. But much of the construction has been unregulated, and managed with the kind of speculative eye that characterises Andrea Camilleri’s sardonic stories of the Sicilian Inspector Montalbano.

Upgrading Lampedusa's facilities

The mayor succeeded in obtaining piped water only two years ago, and many apartments are still not on the network. Her goal is to upgrade the island’s facilities. Confronting her is the island’s reputation, largely from an incident in 2010 when 800 migrants were stranded for three winter months on Lampedusa’s main street, the Via Roma. One of the island's worst tragedies occurred in October 2013 when a boat carrying African migrants from Libya sank off its southern coast, claiming 366 lives. The flotilla of coastguard vessels backed up by a legion of police on land and a discrete, state-of-the-art reception centre just outside the town have all but airbrushed the migrants out of Lampedusan daily life. Forewarned by radar, the coastguard intercept the boats off shore and take their occupants to the reception centre – over 200 were brought ashore three days earlier – and swiftly these poor people are transferred to centres elsewhere in Italy. The efficiency is dazzling.

Rabbit Island

The mayor has another objective: to raise the bar on the island for tourists, adding archaeology to the magic of its beaches. In her mind as she thinks of archaeology is her greatest achievement: in two words, Rabbit Island. Located just off the south coast of Lampedusa, the Isola dei Conigli (Rabbit Island) is one of Italy's last remaining egg-laying sites for the Loggerhead Sea Turtle, a species endangered throughout the Mediterranean.

Surveyed first by William Henry Smith in 1814-16 for the British Admiralty, this tiny offshore stack beside an arcing sandy beach where turtles nest, was home to rabbits, hence its name. Anywhere else in Italy rampant construction would have consumed this piece of paradise. Championed by environmental agency Legaambiente, of which Nicolini is a committed member, it is a swath of coastline worthy of the most majestic in Europe and often tops lists of best beaches. More than this it is an enduring index of how a champion can make a place and so contribute to its economic sustainability.

New museum

Now, add archaeology to the mix of the island’s resources, and Lampedusa can increase the vacationing season, and with it the island’s wider standing. The archaeological superintendency at Agrigento is sympathetic, masterminding a new museum on Via Roma, overlooking the new harbour. The talk is of the alarms, the electrics and winding staircase, then, with less assurance of Lampedusa’s treasures, Greek coins minted here with obverses depicting tuna, a statue dredged from the sea, Maltese Bronze Age farms, a late Roman cemetery and endless treasures secreted underwater. But, like Rabbit Island, there needs to be a vision. Hence, the appeal of Thomas Ashby.

Legacy of Thomas Ashby

Ashby, an inveterate walker, surveyed the island over two days in 1909. He found the remains of Bronze Age huts like those he had helped excavate on Malta and he reviewed the other remains belonging to a place that has attracted every quintessential Mediterranean interest – Punic, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Arabic and, from recent times, the Bourbons, and then of course, featured in the run-up to the Allied landings in 1943 on Sicily when, codenamed Operation Corkscrew, British forces landed here in June of that year.

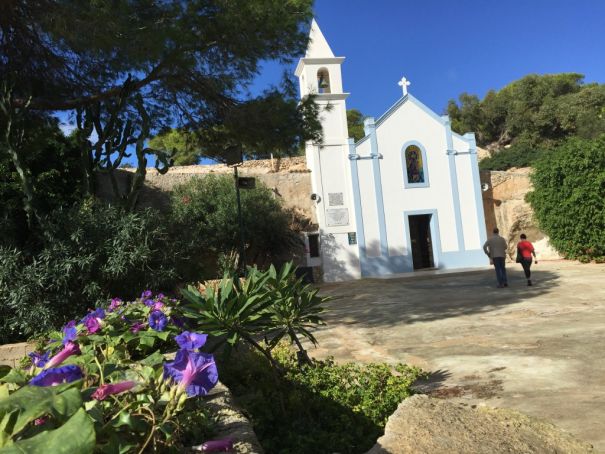

Sanctuary

Two monuments are musts on any visit. Three kilometres west of the town beside the coast road is a sanctuary, a grotto with an elegantly white-washed baroque façade. Dedicated to the Madonna of Porto Salvo, it is all that remains of a collection of mediaeval/early modern cave dwellings occupying this south-facing canyon. The pivotal facility here is a decorated wellhead. Given Lampedusa’s struggle with water supplies in recent times, it is important to note that Greek, Roman and later ships apparently berthed in the waters off-shore to take on sweet water from a network of Lampedusan wells like this.

Lampedusa's heritage

Further west, beyond the track leading to Rabbit Island, just off the road, the European Union has supported the conservation of a traditional dry-stone farmhouse, the Casa Teresa. A longhouse in all but name, as Ashby pointed out in 1909, its broad walls and flat roof belong to an 18th-century Arab vernacular, probably early modern, from the 18th century. In its ensemble of walled gardens is a reconstructed threshing floor, beyond which, occupying the far horizon, is the old American radar station, menaced by Libyan missiles in 1986. The restoration of this farmstead was only finished recently, but already bears the distressing hallmark of inattention; when we arrived the only other visitors were two knaves in military drill illegally trapping finches.

So should the museum on Lampedusa’s main street simply house the odds and ends so far found on the island? Here is the challenge. Rabbit Island is breathtakingly simple in its minimal but well-constructed paths, shaded spots and signage. Designed for visitors with a penetrating perceptiveness of the importance of the views, the crystalline blue sea and the fragility of the sands for nesting turtles, it is a tribute to 21st-century thinking. Shouldn’t the new archaeological museum be as bold and forward-thinking? The walls of the present Archivio Storico on Via Roma, run by a charismatic enthusiast, Antonino Taranto, on behalf of an energetic local society, are covered with photographs, including Ashby’s. This little treasure-house hosts the endless stories that in combination make up the priceless history of this improbable place. That is, all except one story: the one that has lent Lampedusa its notoriety and drew Pope Francis and politicians here, the migrants.

Treasures from the past

Modern Italy has learnt and coped with this ghastly humanitarian crisis. All involved deserve our admiration, as they are learning and acting – perhaps for specific political expedience in some cases – to implement humane best practice. Now, surely the museum should be a portal not only to visiting places on these islands and finding pleasure in authentic treasures from the past, but also an opportunity to explain how the community has been shaped over time, confronting pirates, invasions and, of course, migrations.

I did not meet or see one migrant, but I encountered an exceptional mayor in a place that is indelibly imprinted on my mind. As the plane thrust upwards and weaved around the massing storm clouds to pass over verdant volcanic Linosa, I could not get the sacred beauty of Rabbit Island out of my mind, and I harboured a secret and improper pleasure from my connection to Ashby, a truly great scholar who never wavered from faithfully recording the visceral conditions of people in places.

Richard Hodges, an eminent archaeologist, is president of the American University of Rome and was director of the British School at Rome from 1988-1995.

This article was published in Issue 76 of Current World Archaeology in April 2016. Published in the June 2016 issue of Wanted in Rome magazine.