This article was first published by Wanted in Rome on 15 September 2010 in memory of the Italan military hero who died in June of the same year.

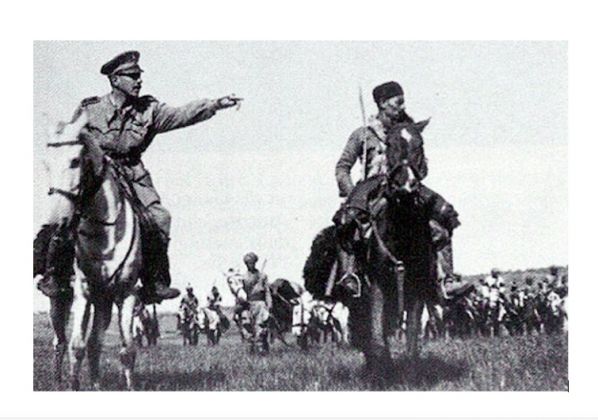

At daybreak on 21 January 1941, only the sentries and the cooks were awake in the British camp outside Keru. Bouyed by their success against Rommel in the Western Desert, the 4th and 5th Infantry Divisions were pressing south into Italian East Africa – today’s Ethiopia and Eritrea. Suddenly the sentries, hardly able to believe their eyes, screamed “Tank alert!” as a horde of horsemen in native dress broke into the camp brandishing swords, hand grenades and molotov cocktails, their leader shouting the Italian battle cry “Savoia!”The intruders slashed their way through the 4/11th Sikhs, and then galloped straight towards British brigade headquarters and the tanks and 25-pound artillery of the Surrey and Sussex Yeomanry. As the British trained their howitzers down to zero elevation and decimated the horsemen, they also wreaked havoc on their own colleagues with “friendly fire” while the surviving horsemen disappeared into the desert. The British army had just suffered its last ever cavalry attack, almost the last in the history of modern warfare.

A few weeks ago, while Rome was struggling with the onset of summer heat, titillated by tales of “escorts” and obsessed with the fallout from the G8 summit in L’Aquila in 2009, the leader of the attack, one of the most highly decorated officers in the history of Italy, passed away quietly and almost unnoticed aged 101. Known as Comandante Diavolo, Amedeo Guillet had led the charge on his favourite white horse Sandor.

Guillet was a colourful and adventurous cavalryman, and has been dubbed “the Italian Lawrence of Arabia”. He was born in Piacenza on 7 February 1909 to a Savoyard-Piedmontese family of the minor aristocracy which for generations had served the dukes of Savoy, who later became the kings of Italy. He spent most of his childhood in the south – he remembered the Austrian biplane bombing of Bari during world war one – then followed family tradition and joined the army.

After graduating from the cavalry academy in Modena in 1930, he was considered a potential gold-medallist at the 1936 Berlin Olympics But Italy was intent on creating an empire in Africa; he volunteered to take part in the occupation of Libya, and then commanded a Moroccan unit in the Spanish Civil War, where he was awarded the silver medal for gallantry. He served there as aide de camp to General Luigi Frusci in the Black Flames division, which was sent to support Franco.

But he was a witness to atrocities on both sides, and deplored what he had seen of Italy’s German allies during the posting. On his return to Italy, he was so distressed by the anti-semitic and pro-nazi policies of the Mussolini government that he requested a transfer to Ethiopia, where the well-respected Duke of Aosta – a family friend – was serving as viceroy.

Here he was tasked with forming a fighting group of Eritreans known as the Bando Gruppo Guillet. Although only a lieutenant, he was virtually in command of a brigade. Dressed in native clothes, he and his horsemen waged an apparently hopeless war against the invading British forces, and yet despite huge losses they were successfully able to hamper the enemy advance and save thousands of lives.

The British finally broke through, defeating the Italian forces at Keren. Most of the Italian army had no option but to surrender, but Guillet – ever true to his oath to the king – refused to do so, and went to ground.

Cut off from the Italian lines, Guillet was forced to go into hiding and wage guerrilla warfare for nine more months against the invaders. His relations with the local populace were so good that he had no fear of being betrayed. In his biography (Amedeo by Sebastian O’Kelly), Guillet tells how he fell in love with Khadija – a beautiful Ethiopian Muslim, daughter of a local chieftain. She elected to ride with him, and together they held up the British lorries heaving up the mountain road to Asmara and blew up the important Aosta bridge.

Despite being hounded by British intelligence officers, and with a price of 1,000 pounds in gold on his head, dead or alive, Guillet went on the run disguised as Ahmed Abdallah Al Redai, a Yemeni beggar, and eventually made it to neutral Yemen. Guillet was able to sneak back to Eritrea in 1943 in disguise, and returned to Italy on a Red Cross ship, where he was reunited with his fiancée Beatrice, whom he had feared he would never see again. The couple married in April 1944 and he spent the rest of the war as an intelligence officer, befriending many of his former British enemies from East Africa.

In the aftermath of world war two, Amedeo Guillet, disheartened, wanted to leave Italy for good. But the king whom he had always obeyed commanded him to stay, so he joined the foreign service. Unwilling to accept “raccomandazioni”, he insisted on taking the regular entrance exam, where he was placed fifth out of 400 applicants for 15 positions. His fluent Arabic brought him postings to Egypt, Yemen, Jordan and Morocco. He also served in India. As Italian ambassador to Morocco in 1971, he was present as a guest when a bloody palace coup interrupted the 42nd birthday party of King Hassan II, leaving 92 guests and members of the royal household dead before loyalist troops arrived to capture the rebels. He was decorated by the Vatican for his organisation of Pope Paul VI’s historic 1964 visit to the Holy Land.

He described himself as the luckiest man he knew – surviving British and Ethiopian bullet wounds, Spanish grenade fragments and a sword cut to the face, as well as numerous bone fractures from riding accidents.

Among his awards were five silver medals, one of bronze for military valour, five crosses of war, Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoia, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, Grand Official of the Order of the Nile of the Arabic Republic of Egypt, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of S. Gregorio Magno of the Holy See, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of Kaukab of the Hashemite Reign of Jordan, and Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Alaouita Reign of Morocco.

He retired from diplomatic life in 1975 to a cottage he had bought in Ireland, to enjoy the foxhunting. His wife Beatrice died in 1990 and is buried in Capua where he is also now laid to rest. Amedeo Guillet is survived by two sons, Paolo and Alfredo.

By Geoffrey Watson

Note: A stirring account of his life was broadcast on RAI in 2008, and can be seen on YouTube.

And many thanks to James Walston for pointing out the delightful obit (in Italian) by Vittorio Dan Segre which I missed when it appeared in Il Sole-24 Ore. To read Segre's appreciation click here For Geoffrey Watson's blog click here.

Also check Amedeo by Sebastian O'Kelly