MAXXI celebrates the legacy of Italy's foremost "radical architecture" group.

Jacopo Benci

The exhibition Superstudio 50 at the MAXXI in Rome celebrates the 50th anniversary of Superstudio, the most iconic among the groups of Italian “radical architecture” (a term coined, like arte povera, by critic and curator Germano Celant). Most of the radical architecture groups – Superstudio, Archizoom, Zziggurat, Ufo, 9999 – were born in 1966 and immediately afterwards, and hailed from Florence.

Though it had been the cradle of many epoch-making innovators (from Giotto, Masaccio, Brunelleschi, through Leonardo, Michelangelo, Galileo, up to the Florentine futurists and beyond), in the postwar years Florence was fettered by a cultural conservatism that was opposed by intellectuals such as architects Leonardo Ricci, Leonardo Savioli, Leonardo Benevolo, Giuseppe Gori, Giovanni Klaus Koenig, composers Giuseppe Chiari, Pietro Grossi, Sylvano Bussotti, and anthropologist Tullio Seppilli (some of whom taught or befriended the future members of Superstudio), and by the growing unrest of the generation born around 1940. This was compounded by the trauma of the catastrophic flood of the Arno on 4 November 1966.

Superarchitettura

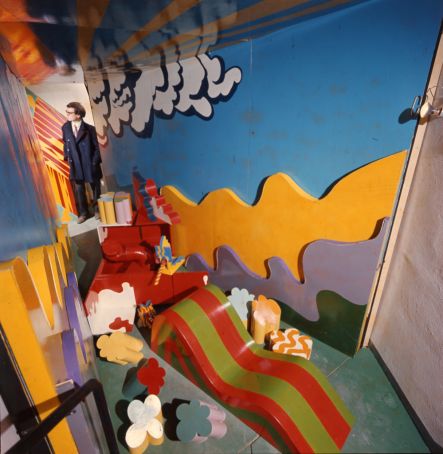

Superstudio came into being at that very moment, when architect/painter Adolfo Natalini accepted his architect/photographer friend Giuliano Toraldo di Francia’s invitation to share a studio on the Bellosguardo hill, after Natalini’s studio in town was flooded. On 4 December 1966, a month after the flood, an exhibition called Superarchitettura opened at a small art gallery in Pistoia, presenting an environment involving prototypes of furniture, objects, lamps strongly linked to pop art, created by Natalini – who exhibited under the name Superstudio – and a group of fellow architecture graduates led by Andrea Branzi, who took the name Archizoom. Between 1967 and 1970 Natalini and Toraldo di Francia were joined by Roberto Magris, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris and Alessandro Poli (who left in 1972).

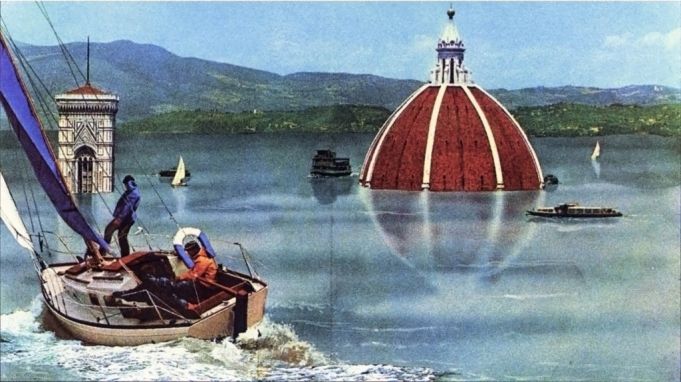

Throughout their activity spanning over 12 years, Superstudio never ceased to cross borders and break down walls between disciplines. Their “superarchitecture” phase (1966-68), consisted primarily of objects, lamps, furniture, sofas making use of industrial materials like polyurethane foam, coloured perspex, fibreglass, retaining a strong link to pop art. This gave way to a simplified “technomorphic” architecture (1967-68), inspired by contemporary monuments such as Cape Kennedy’s Vertical Assembly Building; the process of reduction then led to the adoption of a 3x3cm grid, design stripped down to its essential constituent elements, which became the base of the Misura/Quaderna furniture (1969-70), the Architectural Histograms (1969) and then developed into the planetary scale of the Continuous Monument (1969-70) which Superstudio painstakingly represented in images created with collage, drawing, airbrush, translated into an extraordinary series of colour lithographs.

Continuous Monument

Superstudio members were acutely aware of the role of images when they wrote: “the myths of society take shape in the images society produces. The new objects are both things and images of things.” Although some of their projects for industrial buildings, houses, discotheques, shops and commercial spaces were built, and they participated in several national and international architectural competitions, their most widely known and influential production were the ideas, masterfully translated into memorable visual representations.

The Continuous Monument – which was never meant as a celebration of the architectural mega-structure, but as the denunciation of its intrinsic connection with power and control – was abandoned as Superstudio’s critique of architecture and the built environment led them to the dystopian “cautionary tales” of the Twelve Ideal Cities (1971), and further on to outline the possibility of a different form of existence, based on a planetary “supersurface” equipped with a network of energy supply points, which would provide support to the Fundamental Acts of existence: Life, Education, Ceremony, Love, Death (1972-73).

Natalini had already pointed to this in a 1969 statement: “Modern furniture seems like a great race towards the most beautiful, the newest, the most functional. But no matter if one arrives earlier or later, the race is wrong. Therefore, the thing to do is not to participate in the race, but to get away from it as soon as possible, and isolate ourselves, slowly to pick up the pieces of our lives and fashion the tools for survival, in order to meet the true needs.”

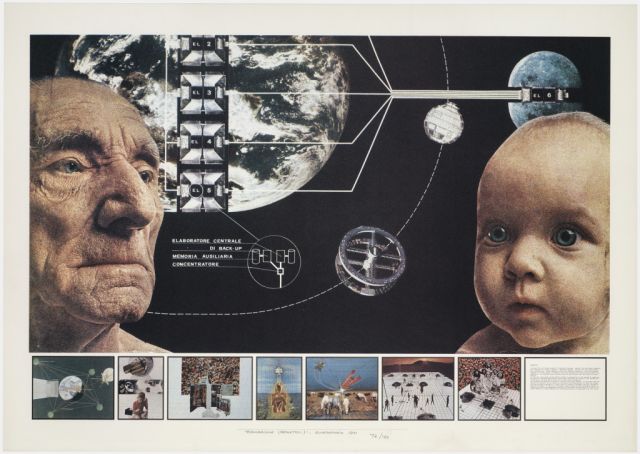

Fundamental Acts

A series of lithographs was created for Fundamental Acts, and a cycle of five short films was planned, of which only two were realised, Supersurface – Life (1972) and Ceremony (1973). Even in using the film medium, Superstudio combined different languages and techniques: still images shot with a rostrum camera, stop-motion animation, filmed segments (in Ceremony, members of Superstudio performed for the camera), with texts read in voice-over and in Ceremony, the use of Music with Changing Parts by Philip Glass.

Gian Piero Frassinelli, whose 1968 graduation thesis already combined cultural anthropology with architecture, played an important role in Superstudio’s shift towards a more markedly anthropological slant. He wrote all the texts of the Twelve Ideal Cities, which also reflect his and his colleagues’ interest in science fiction.

Superstudio’s late work included the installation The Wife of Lot (exhibited at the 1978 Venice Biennale alongside Zeno’s Conscience, an anthropological investigation of an old peasant’s material culture). This consisted of a zinc table with five models of monuments made of salt (a pyramid, a colosseum, a cathedral, the Versailles palace, Le Corbusier’s Pavilion of the Esprit Nouveau), slowly dissolved by water dripping from a suspended container; the salt water ran into a bin that contained the word Oblivion. The installation bore the subtitle “Architecture is to time what salt is to water.” When the last salt architecture, the Pavilion, was dissolved by water, it revealed a small plaque with the phrase “The only architecture will be our life.”

Italy: The New Domestic Landscape

Unlike most Italian intellectuals and artists in the postwar decades, Natalini and Toraldo di Francia spoke English. Natalini often went to London where he discovered the works of Phillip King, Derek Boshier, Joe Tilson, Eduardo Paolozzi, but also the projects and publications of Archigram. Toraldo di Francia lived in the United States in 1953-54 when his father Giuliano, a physicist and philosopher of science, taught in Rochester. This made it possible for Superstudio in the early 1970s to be invited to lecture at the Architectural Association in London (through the enthusiasm of young AA graduate Rem Koolhaas) and at Rhode Island School of Design (at the invitation of RISD faculty Friedrich St Florian), and to participate in the seminal 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the MoMA in New York.

In Italy, conversely, Superstudio and radical architecture were attacked by authoritative critic and historian Manfredo Tafuri, who in his widely read books Progetto e utopia (1973), Architettura contemporanea (1976) and Storia dell’architettura italiana (1985) dismissed their works as “self-advertising exercises”, “late-romantic longings”, “orgy of graphic patterns”.

The re-discovery of Superstudio in Italy began in the mid-1990s when a younger generation of architecture students came across the group’s texts and images in old issues of Casabella and Domus.

Superstudio 50

The exhibition Superstudio 50 – curated by architect/historian Gabriele Mastrigli, who has researched Superstudio for several years – provides the most complete overview of the group’s work and includes a wealth of rare or previously unseen material. A monumental red wall specifically designed by Superstudio forms the backbone of the display; and Il Monumento Continuo, the group’s first film project conceived in 1969 but never realised, is presented as a digital animation made in 2015 by video artist Lucio La Pietra following the original storyboard.

The exhibition is accompanied by a definitive monograph, Superstudio. Opere 1966-1978 (Quodlibet), an 800-page volume with 545 illustrations. Edited and with an introductory essay by Mastrigli, the book presents Superstudio’s work in chronological sequence and includes contributions by all three surviving members of the group. Cristiano Toraldo di Francia’s text reconstructs the “prehistory” of Superstudio and its relations to Florence. Besides being an essential companion to the exhibition, the mongraph provides the foundation for any further research on a key component of contemporary Italian culture at large.

The Superstudio 50 exhibition can be visited until 4 Sept, for details see website. MAXXI Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI secolo, Via Guido Reni 4, tel. 0632810.