A culinary guide to Rome through its art galleries.

Painting and food: Rome, of course, abounds with both. But painting about food – and its sine qua non – wine? This article offers a sort of Gambero Rosso to just that in some of the city’s galleries and museums, in more or less five courses.

First course is the painting Il Gusto (Taste) by Jusepe de Ribera, known more often as Lo Spagnoletto. Admittedly it was sold to Spain long ago with most of the painter’s other works, in this case ending up across the Atlantic. It now hangs in Wadsworth Athenium in Hartford USA. Yet the setting is eminently Roman, in this case less Via Veneto than low-life trattoria, one star not five, perhaps on Via Margutta, where the Spanish artist lodged between 1613-1616 with northern colleagues such as Valentin de Boulogne, Dick van Baburen and Hendrik Terbuggen.

Visit Pigneto or Tor Pignattara – name your suburb – and the subject depicted is still there. Talk about pugnacious and in your face. The cut-price gourmet is as famished as ever, living to eat. His glare from the frame seems to say “So’ romano, chi sei, spagnoletto?”, if only looks could speak. The artist seems to take the insult on board but delights in it. Those tarnished anchovies nearing their sell-by date replicate the bright sheen of the eater’s shirt and threaten to venture into the realm of L'Olfatto (Smell), another of the artist's paintings complete with onion and garlic in a commissioned series portraying I Cinque Sensi (The Five Senses).

Chiaroscuro for the taste buds, olives spill from their roll of paper; some bread demands to be plucked from Il Gusto and eaten. The wine is surely Castelli Romani. The subject’s massive right fist holds a wine-glass, his left a demi-litro held at an angle with no time for niceness. One false word or brush-stroke and you sense that he could launch it like a grenade. “Salute, buon appetito,” one can imagine the Spanish painter remarking, safe behind his precision gaze as his sitter responds with a burp, his fish-breathed laugh defusing another brawl.

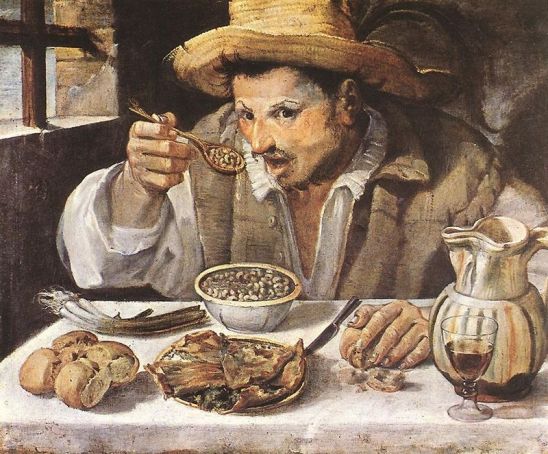

Next up is soup. Annibale Carracci's painting Il Mangiafagioli in Palazzo Colonna upstages an array of ten-a-penny counts and cardinals, even the odd pope or two. With a purposeful crouch, he tucks in with a gusto to make all that silk and purple of the surrounding portraits seem humdrum. “Grub first, art (or class) later,” to rephrase an Auden poem. Continuing regardless of angels and low-flying putti with which the museum is also packed, here’s an example of appetite eclipsing the sublime, levelling delusions of grandeur in its course.

The third course is served by Carracci’s fellow Bolognese and one-time master, Bartolomeo Passerotti. (Such was Passerotti’s influence that the Bean Eater was long attributed to him, rather than his more famous pupil.) In Palazzo Barberini, Passerotti's paintings have a whole wall to themselves. Influenced by the Dutch, who had established a tradition of tabletops heaving with highly-detailed plenty, in La Pescheria (The Fish Stall), Passerotti swaps the tabletop for a fishmonger’s bench. A larger than-life lobster threatens to slither over and drop on to the museum floor. Next to it a turtle peeks from its basket while a decapitated head (some innards still attached) bears witness to a customer who got away. In its detail the painting is something of an Aladdin’s cave. Shellfish of all shapes are depicted with loving care. Human interest comes from an old man getting an earful from an old woman who is also holding up a blowfish to his ear. Look again and there in one corner a cat eyes up a sparrow, or passero – the artist’s hallmark – destined to remain ever beyond its reach.

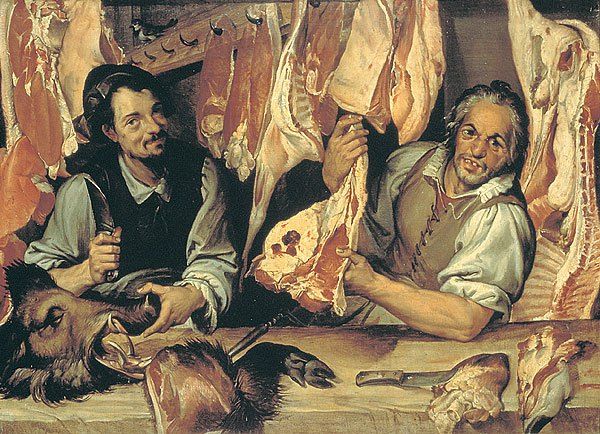

In La Pescheria’s sister picture, La Macelleria (The Butcher) meat hangs like drapery, the butchers' toothy smiles and pride in their profession not a little disconcerting.

No meal comes without a plentiful supply of wine. In a baroque trattoria there’s no shortage of supply. In the next room of the same gallery (Sala 20) in Palazzo Barberini, Bartolomeo Manfredi's Bacchus dangles grapes above a wine-bibbing devotee, glass / chalice taking pride of picture, the bibber’s mouth slightly goat-like.

More famously, in Palazzo Borghese, if Caravaggio’s Bacchino Malato (Sick Bacchus) is disquietingly lifelike, it’s because the godling is also a self-portrait during a bout of illness. His skin is a greenish-blue so that the grapes he holds with a soily thumb seem somehow a part of him. Not the merry figure of some paintings, more a study in deep-rooted compulsion, hangover and thirst in one. The grapes (and a couple of apricots) are a still life in themselves, eminently pickable. They also signal the Italian adoption of an art form in which precision-eyed painters from Holland excelled.

There was a colony of Dutch painters in Rome to pass on their tricks of the trade. They were also great topers, forming bacchic brotherhoods whose strange, wine-fuelled rituals feature in Roeland Van Laer’s painting Les Bentvueghels dans une auberge romaine at Museo di Roma Palazzo Braschi. The wine here is in two flagons balanced on the head of the red-stockinged hostess, while to the side a writer daubs graffiti to Venus and Bacchus, and several boozy acolytes sprawl in the foreground.

Less course than post-prandium is the mosaic of an unswept floor now in the Vatican Museums. This is in fact a copy of a Greek original (by Sosus of Pergamum), such mosaics also becoming something of a fashion in Romae’s triclinii (or dining-rooms) in the second century AD.

Proving that anything that painting can do a mosaic can equal, the remains of an ancient Roman banquet scatter the ground as fresh as the careless moment they were dropped. After 1,800 years even their shadows are still intact. A lettuce leaf, nutshells, molluscs, sprigs of cherries, a fishbone. Enjoying a banquet of its own, a mouse in the right corner advances towards a morsel, appetite immortalised. And lest the diners forget in their cups that this is only trompe-l'œil – Roman wine was very strong – between the scraps the odd theatre mask or two acts as a reminder.

Salute then, another buon appetito. Here’s food for both mind and eyes, without worries over excess calories or tomorrow’s hangover.

By Martin Bennett

This article was first published in the October 2015 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.