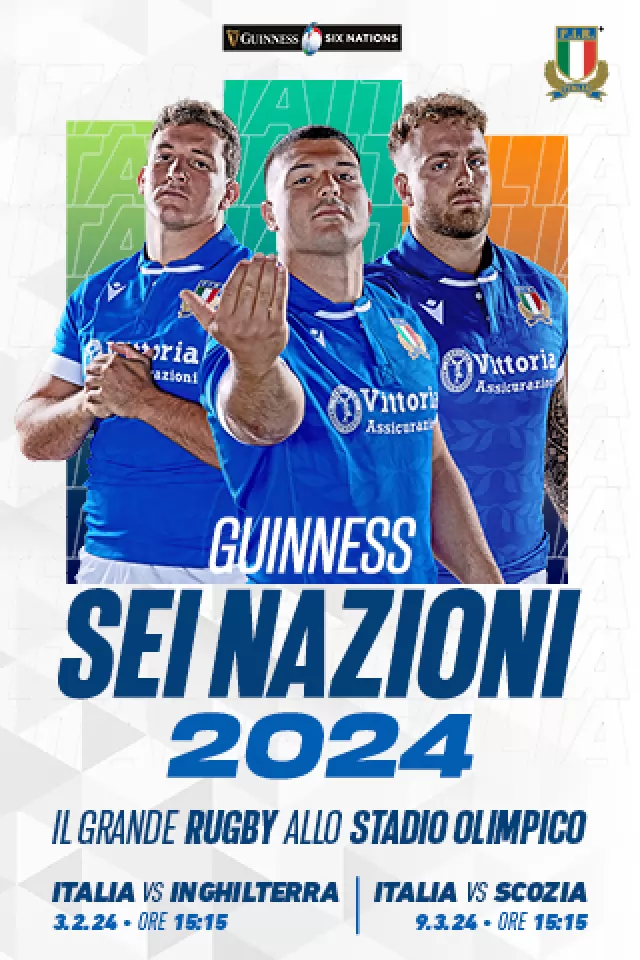

Rome flies its rainbow flag

Almost as soon as prime minister Silvio Berlusconis government hoisted Italys green, white and red tricolore to the mast of war in mid-winter, the multi-coloured rainbow flag of peace began to flutter over the streets of Rome. While the national and the European Union flags still hung side by side over all official buildings the rainbow flag of peace advanced through the rest of the city. In the historic centre it conquered new territory almost daily, appearing on apartment windows, shop fronts, newspaper stands, souvenir stalls and political posters. Its colours were taken up in t-shirts, hair-bands, scarves and other items of clothing. It was held high in demonstrations by young children and pensioners, students and trades union militants, opposition politicians, school teachers and housewives. At one time the flag was in such demand that supplies ran out. According to one newspaper poll taken soon after the outset of hostilities, 72 per cent of those questioned disagreed with the war.

As the invasion of Iraq began on 20 March the rainbow flags took to the streets and squares again, but in a much more muted way than during the weeks that had preceded the outbreak of hostilities. During the first few days of war the mood seemed more cautious. While angry protestors marched in London, in Madrid, in some United States cities and in numerous Middle and Far Eastern capitals, in Rome the demonstrations were calm and orderly. On the first day of the invasion, the atmosphere along traffic-free Via del Corso felt more like the normal evening passeggiata than a protest against the war. The security forces were more evident than the marchers, and noisy motorini drivers lost their patience with the demonstrators for holding up the traffic. A weekend march for peace was marred by bickering among opposition politicians, trades unions and civil society organisations, and the sight of some of them demonstrating in Piazza del Popolo and others in Piazza Venezia might have been comic if it hadnt been so sad.

On the first Sunday of the war Romans seemed to have other things to do: stroll in the spring sunshine, watch the annual marathon or catch a glimpse of the pope beatifying another five faithful. The streets were clear of protests, and the main interest seemed to be in the constant television coverage of the war.

But by the time this edition of Wanted in Rome reaches the newsstands at the beginning of April the mood will most probably have changed again. If the coalition forces have secured the surrender of Baghdad, Berlusconi will be telling Italians that the country has made a major contribution to the cause of world peace. The flags of protest will be rolled up and stored in the cupboard for another day. If, on the other hand, the coalition has made little progress then Berlusconi, mindful that there are regional, provincial and municipal elections coming up in May, could change his tactics and emphasise instead that Italy is after all only a non-belligerent partner to the war.

The US president and the British prime minister declared in the first few hours of war that the battle would be long. But in this modern media age time is not on their side. The images on television are ruthless and the competition among war reporters is intense. Even in the first few days of hostilities Italys women reporters at the front had beaten their American and British colleagues to the news. The first images of bombing over Baghdad came from Italian state-run television RAI. News of a slowdown in the advance of coalition ground forces in the face of stronger resistance than expected from Iraqi troops was aired on Raiunos programme Porta a Porta the evening before BBC World broke the news. Coverage of the hunt along the banks of the Tigris for US airmen thought to have been brought down over Baghdad was shown on RAI several hours before it was screened by the BBC. And, in a tough but right decision that disregarded US and British sensibilities, RAI was quick to air the films of American prisoners of war and dead on its main evening news. It was only when the moral indignation wore off that people began to ask whether this was any worse than showing Iraqi soldiers kneeling in the sand, trussed tightly like chickens for all the world to see. And hadnt captured allied airmen, including two Italian pilots, been paraded before the cameras under similar conditions during the previous Gulf war without such indignant protests from Americans?

Perhaps under this constant barrage of images there is a danger that we shall become immune to the horrors of war. Perhaps we shall become instant armchair strategists and see a complex war in far too simple terms. But there is little danger that we shall become complacent. During the Vietnam war, reporters took several years to bring the conflict from the battlefield into the living rooms and out onto the streets back home. Now it could be a question of a few weeks, maybe only days, before Romes rainbow warriors leave their television sets behind and move back onto the streets and squares of the city to pursue the cause of peace.

Picture: Rome's rainbow warriors hold high the flag for peace. Photo by Andrea Stazi.